Music writer and journalist Joachim Mischke knows his way around the Elbphilharmonie like few others – since the foundation stone was laid, hardly a week has gone by when he wasn't either backstage or in the auditorium. To mark the Elbphilharmonie's fifth anniversary, he has written something close to a love story – 25 individual stories that take the reader way behind the scenes and into hitherto unknown corners of the building. These appear in a beautifully produced volume illustrated with photos by Thomas Leidig, published by Hoffmann und Campe. Chapter 5 tells of the »waiting rooms at one remove from the present« on the 12th floor:

Playing in style: the artists' dressing rooms

The interior styling of the two most prominent dressing rooms behind the stage of the Grand Hall is plain and luxurious at the same time, minimalistic and almost invisible. White walls, a light wooden floor, cream-coloured furnishings. No faded concert posters from the last century reminding one of how everyone used to be better, and certainly more famous; and no abstract paintings that were going cheap by the dozen. Just a couch, a table and chair with a phone and a shower. Really a bit spartan at first glance. Only two special details betray that this is not a hotel room, and not a personal refuge either: one is the monitor on the wall showing the arena outside the door, and the other is a towel awaiting use on the rack in front of the big mirror, carefully folded and brilliant white. A discreet signal with best wishes from the management. A reminder that, much as the artist may love music, he is not just here to enjoy himself. A reminder that art under this roof is hard work that makes one perspire.

Perhaps such towels have already been used to wipe away not tears of joy, but tears of existential despair: no-one knows for sure, and that's probably for the best. What goes on in the dressing room stays in the dressing room. This is where an inconspicuous young woman changes into a dazzling virtuoso whose charisma upstages an orchestra as if there was nothing to it. This is where a famous conductor shuffles in unrecognised in his gardening clothes, quickly steps into his black tailcoat and is ready to go right on time, like Clark Kent when he takes off from the phone box to save the world in his Superman gear.

Depending on the artist's personality, a dressing room can also be a place for socialising, for a relaxed chat. William Christie, a conductor who specialises mainly in French Baroque music, didn't lose his cool for a moment during our long interview just before the concert started. And the meeting with Herbert Blomstedt possessed an old-world calm and charm. One anecdote followed another, with Blomstedt's ancient briefcase on the table as a sign of his composure while the 92-year-old conductor talked about his profession and the vocation it entails. With younger artists, the briefcase tends to be replaced by a smartphone or an iPad containing everything they need to know. An encounter with pianist Yuja Wang during the interval was the opposite of the high-heel gloss that one might have expected. This was a fragile young woman with a slight dose of the flu who had just worked really hard, and was probably happy to have got through the performance without fluffing it. »Playing« a concert is a serious slice of understatement: »giving« a concert is a better description, for the artist literally gives his all.

These waiting rooms at one remove from the present – there are seven of them on the 12th floor, each with its own bathroom – are worlds away from the historic ego-architecture of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus; but a good 50 metres above the River Elbe, Wagner's weighty incentive still applies: »We are here in the service of art.«. The whole thing is one single projection screen, an exercise in concentration turned into a waiting room. There is nothing, apart from the super view of the docks through the floor-to-ceiling windows, to distract one from the leitmotif of creative existence. Just a few metres away, the concert platform is waiting, both alluring and threatening. And the audience is eager to hear and see the performance and to take something away from it; they want to return, moved and changed by the concert experience, to their lives, which are undoubtedly very different from that of the person in the dressing room.

Out in the corridor there is a practical little clip-on name tag on the wall next to each dressing-room door, so that the name can be changed quickly in a season where maestro A is followed by soloist B in rapid turnaround. No-one has a chance to get settled here: there is a constant coming and going. Every occupant fades away, but still lingers on, soundlessly.

The rooms behind the stage are some of the most sensitive cells in the entire body of the concert hall. They are the only place where an artist can be and remain completely alone, if he wants to or has to. One can enjoy or endure the solitude, the boundaries here are probably fluid. No-one is admitted without an express invitation. There's no bouncer on the door – you can't get into the backstage area anyway without a coded keycard. There is just an unspoken etiquette of immense politeness: knock on the door and wait – don't charge in without being invited. Everyone understands the rule, which applies equally to assistants of many years' standing, to friends and to the stage techician on duty at the time. The magic word here is respect. Respect for the will to achieve, for the yearning, the hunger for beauty.

Der Autor: Joachim Mischke

These dressing rooms are not offices that you can just rush into in search of some missing files. These dressing rooms are reservations, sanctuaries for sensitive artists, the first place of refuge when the concert's over. They may be a place of rescue after an evening that wasn't so great. In that case, any visitor during the interval will find himself staring at a closed door with the depressing message: »I tried my best, I really did. Now I need to take a deep breath – I'll be right back«. But the door may also be be a rest sign before the conductor in the next room knocks, all worked up and in a euphoric sweat that the concert went so well, to invite the artist to join him on a big tour. The local concert promoter or the director of the concert hall might be waiting outside the door to suggest not just a single concert next time, but an entire series.

Carefully organised from a psychological point of view and deliberately arranged within the architecture of the building, the soloist's dressing room No. 12.1 is a little bit higher up the food chain than the neighbouring room. No-one else has such a short and direct path from his sanctuary to the limelight, even if it's only a difference of a few inches. Open the door, round to the left, pass the stage manager's desk and then it's the first (and only) door on the right. Much too short an approach path to work up any real stage fright, but at least it's long enough for the artist to use it as a launching pad for his own blood pressure. Then there's another practical detail that wasn't neglected when designing the dressing rooms: behind the grand piano in the soloist's room there is a door in the side wall leading to the Green Room, the antechamber for those chosen special guests who hold little audiences there, shaking hands, posing for photos or exchanging other friendly gestures. Grouped around the auditorium, as close as necessary, are the tuning rooms for the different groups of instruments in the orchestra. This was another idea prompted by the principle of customer service inherent in the building's special architecture. In many concert halls, these rooms are in some corner of the building where there was space for them. They are rarely attractive and generally full of orchestra equipment, with plaster peeling off the walls. Daylight is a rare feature. These are purely functional rooms where the artists change, where they store in their lockers spare parts for their instrument, sheet music and rehearsal notes, maybe some snacks and a talisman, or even the shopping they did before the rehearsal.

Like so many things in the building, the lockers at the Elbphilharmonie are tailored to fit the size of instrument concerned at the wish of the NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchestra, which, as orchestra in residence, is the most frequent user. The cellists and double-bass players have a tough enough time anyway, so they have been allocated a room right next to the stage entrance on the north side of the building. A room that is not only spacious and well lit, but also offers a panoramic view that managers in the neighbouring office buildings would die for. To the south, the room looks out over the Elbe and the docks, while the view to the north takes in the »Michel« church and the city centre. An unobstructed view in a top location – you couldn't do any better in the entire world of classical music. For the leader of the orchestra there is a separate section just a few doors to the left of the conductor's room.

On the 11th floor there are four group changing rooms and another eight tuning rooms. All in all, soothing for the orchestra's ego. And absolutely no comparison with the unworthy surroundings that the musicians had to put up with for decades in the backstage area of Hamburg's Laeiszhalle. These dusty corridors, amidst all manner of boxes, were often the only place where the performers could slip into their evening dress, as if they were just passing through and not regulars at all.

One thing that's vital for group dynamics, here as everywhere, is the cafeteria. Musicians are only human, after all. It's just a few steps away down the corridor, and the view could have come straight out of a movie: the glass façade is an ideal sedative for the coffee break, and the architects included a little balcony right next to the counter. Here, too, the room is furnished in plain white; the lounge sofas are almost the size of a single bed, separated by high room dividers so that colleagues can't overhear your conversation. On the right there is a metre-long sideboard that will accommodate a buffet big enough to feed an entire orchestra when it streams out of the tour bus and into the building. The area is nice and airy: there are transport boxes standing around, but they're not actually in the way. Music stands not in use at the back of the stage find a new use: if some members of the brass section are not needed yet and they don't want to miss an important soccer game, they rest their smartphones on music stands until it's their turn to play.

These looks at the backstage area tend to lose their mystique in the case of the machine room, but they are still touching. Normal as things may be there, the next minute the elevator grinds into operation just a few yards away. And on the opposite wall, some 12 metres wide, former NDR viola player Rainer Castillon responded with a neat idea to a suggestion that came straight from the Elbphilharmonie architects: the instrument storage area, decorated with light brown silhouettes of stringed and wind instruments. When musicians are taking a quick break, they can park their trusty partners there and keep an eye on them.

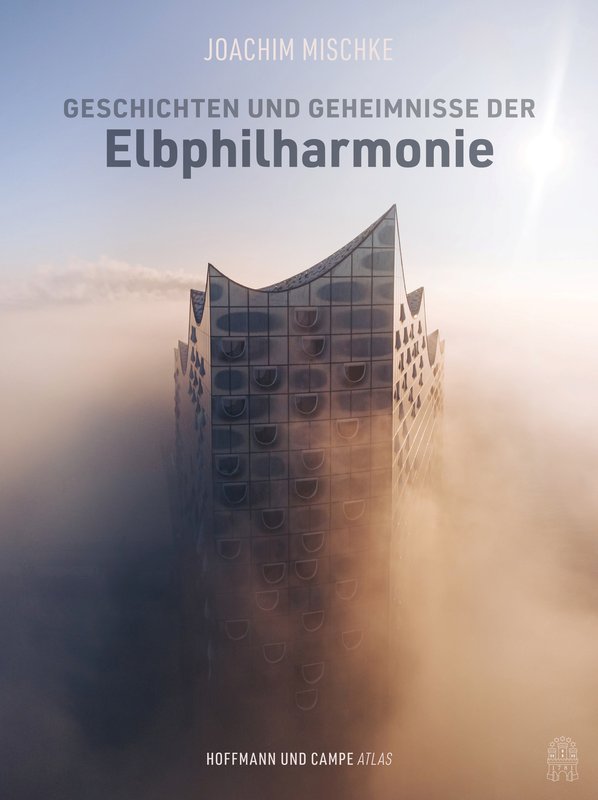

Joachim Mischke's book is available to buy at the Elbphilharmonie Shop on the Plaza, in bookshops or of course from the publishers Hoffmann und Campe. (Available only in German)

Joachim Mischke

Geschichten und Geheimnisse der Elbphilharmonie

176 Seiten, gebunden mit Schutzumschlag

durchgehend farbig, mit vielen Fotos

26,00 (D)

26,80 (A)

34,90 (CH)

ISBN: 978-3-455-01257-6