Text: Ivana Rajič, November 3, 2025

See Venice and die? For Helmut Lachenmann, it’s the opposite: to be reborn – at least artistically. In 1958, the 21-year-old moved to the city of canals in order to drift as in a labyrinth of waterways and bridges, to try out routes, to allow detours and ultimately to find his own sound. Time and again, he reinvented traditional instruments, discovered unimagined sounds and ways of playing and made the physical material of the sound itself the subject of his music. No one else has so radically expanded the soundscape of the classical orchestra, no one has thereby pushed into the unknown with such passion. Today, the Stuttgart native is regarded as the most important living German composer. His works are played worldwide, his aesthetic approach influences generations. And yet he has retained his wonder, curiosity, adventure. On 27 November 2025, Helmut Lachenmann will be 90 years young.

Spotlight: Helmut Lachenmann :Season 2025/26

Ein Abenteurer der zeitgenössischen Musik wird 90 und das muss gefeiert werden! Helmut Lachenmann prägt mit Entdeckergeist und Experimentierfreude die Neue Musik.

The son of a pastor encounters the young savages

»Born in Stuttgart, parish house, a lot of siblings, a lot of stimuli, a lot of music. war, post-war period, piano lessons, boys’ choir, composing, secondary school, books, scores, Abitur [‘A’ levels] and the start of his music studies« –Lachenmann once encapsulated his early years so succinctly. From 1955, he studied the piano in Stuttgart under Jürgen Uhde, theory and counterpoint under Johann Nepomuk David – teachers firmly rooted in tradition and academically conservative. The first work accredited to Lachenmann, »Fünf Variationen über ein Thema von Schubert« [5 Variations on a Theme of Schubert] for piano, is regarded as the only evidence of his earliest style: based on the classical variation technique, he unpicks Franz Schubert’s »Deutschen Tanz« [German Dance] in C sharp minor into an almost Beethoven-like style in order to reassemble it.

Franz Schubert’s »German Dance« in C sharp minor

1. Variation from Helmut Lachenmann’s »Five Variations«

Soon, however, the centres of the contemporary avant-garde – the Darmstadt Summer Course of New Music and the Donaueschingen Music Festival – become more important to the young composer. There, he encountered the intellectual heads of a new musical world: Pierre Boulez, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Bruno Maderna – composers who, after 1945, challenged everything that came before. Their method of composition: serialism – a strictly regulated music in which not only the sounds, but also their duration, volume and timbre are methodically organised. Nothing is left to chance: music becomes the specific architecture in which each note is a building block in a larger system.

Resurrection as the avant-gardist

In Darmstadt, in 1957, Lachenmann met a composer who was to influence him not only artistically, but as a human: Luigi Nono. He followed him to Venice a year later in order to study under him. The Italian taught him that music is not just an abstract structure, but always also an attitude towards the world. You have to be politically awake, ethically responsible, internally authentic, according to Nono. When Nono looked into Lachenmann’s scores, he is supposed to have said: »Out with these melodic expressions!« – a challenge to get rid of old habits. Under Nono’s influence, works like »Souvenir«, »Fünf Strophen« [Five Stanzas] and »Echo Andante« for piano solo came into being. With the latter, in 1962, Lachenmann gave his public debut as composer and pianist at the Venice Biennale and the Darmstadt Summer Course – and gained recognition overnight in the circles of the avant-garde. Here, he is indeed still guided by Nono’s classification system of sounds, but he smoothes his erratic sound movements and lets major and minor colours shine through between the dissonant, strained harmonies. Towards the end of the work, a pure C major chord, for example, clearly pierces through the acoustic space in triple forte:

»For me, the note is not ›C sharp‹ or ›C‹, but I hear the energy,« Lachenmann explains later. And, already with »Echo Andante«, it becomes apparent what will become his trademark: the attentive listening to the physical emergence of the sound. The notes are carefully scored, their mode of attack – tender, harsh, distorted – becomes the compositional means here and demonstrates how its »energy« can be made to take shape.

From the sound to the body :the »musique concrète instrumentale«

At the end of the 1960s, Lachenmann finally finds a term for what he does: »musique concrète instrumentale«. An unwieldly concept, which, however, means something quite simple: music which takes the specific nature of its sound production as its starting point. What French composer Pierre Schaeffer made in his »musique concrète« with tape recordings of real everyday sounds, Lachenmann transfers to classical instruments. His sound sources are not motors, bells or railways, but violins, trumpets and trombones.

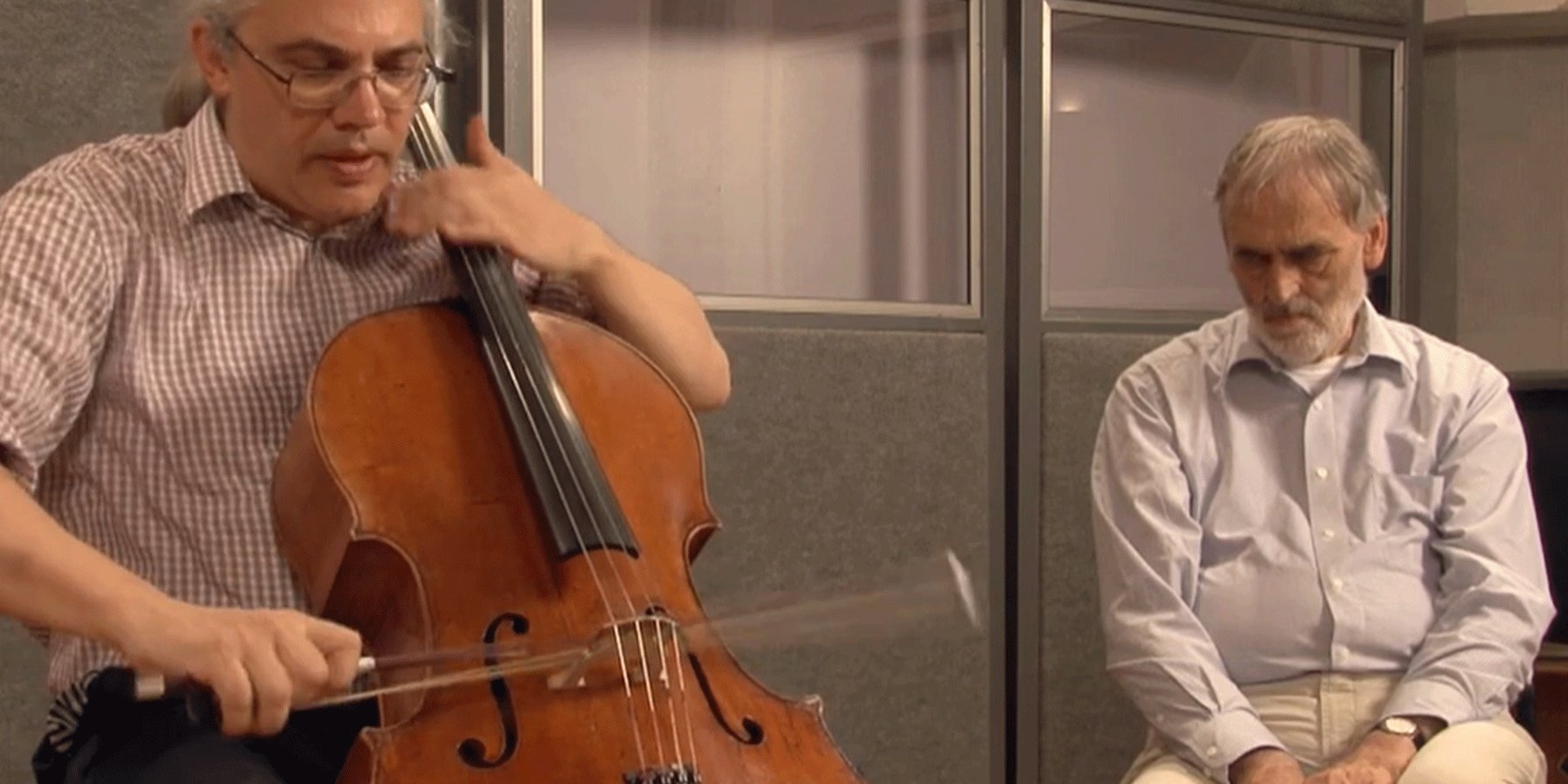

The musicians no longer play on their instrument, but with these methods: scratching, stroking, tapping, rubbing. Music emerges from the materiality of the instrument so that making the distinction between »beautiful« and »ugly« is superfluous. Lachenmann wishes to liberate the specific sound as far as possible from any conventions and listening habits. Many of his works of that time bear titles which refer to movement or energy – »Pression« [“Pressure”] for cello (1969/70), »Guero« [referring to a Latin American percussion instrument] for piano (1970) »Dal niente (Intérieur III)« [“Out of the blue (interior III”] for clarinet (1970), »Schwankungen am Rand« [“Oscillations on the edge”] for sheet metal and strings] (1974/75). There is always the same momentum behind it: to create the moment in which a sound is born.

Lucas Fels plays Helmut Lachenmann’s »Pression«

»Pression« is the first of his wanderings through a host of such individual technical playing situations. »Until then, it had not yet been so relentless,« says Lachenmann about this work. »I had to modify this playing where you hear the sound as the result of its production. This meant, for example, that you do not just simply press or sweep the bow, but that you search for all possible options as to how energy can be converted onto this instrument – be it on the strings, be it on the tailpiece, be it behind the bridge.« In »Gran Torso« (1971), Lachenmann deployed this assortment of playing techniques – from the almost inaudible sliding sound of the fingers to the most massive bow pressure – initially on all four instruments in the string quartet – as a smashed monument of the most classical of all genres.

»This left a distinctive impression on people,« understates Lachenmann. His »musique concrète instrumentale«, which became the defining aesthetic of his works by the end of the 1970s, often unleashed mental disturbance and fierce opposition. Many people had previously reviled him as an instrument tormentor. His experiments were, thereby, never an end in themselves. Because, for Lachenmann, it was less about new sounds than about a new way of listening.

Overriding the musical past

The familiar sounds of the past must, therefore, also disappear. This pained the audience, for instance, at the premiere of »Accanto« for solo clarinet and orchestra (1975/76). From Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto in A major, minimal, alienated sound fragments are recorded on tape here – the once loved concert favourite is now transformed into an unpleasant noisy state. In a single passage, this excerpt is not made unrecognisable, but combined with a vocal action of a somewhat coarse style. »My piece is accanto: in addition,« says Lachenmann very dryly about it. His work becomes the tool to raise an objection against confusing beauty with the conventional. A »disruptive handling of what you love in order to keep its truth,« the composer calls it.

What started with orchestral works, such as »Accanto« and also »Tanzsuite mit Deutschlandlied« [Dance Suite with National Anthem], continued into the 1980s: a clearer, albeit certainly now ever critical/analytical link to tradition. The title of his String Quartet No. 2 »Reigen seliger Geister« [Dance of the Blessed Spirits] (1988/89), for instance, already refers to Christoph Willibald Gluck’s »Orfeo ed Euridice«. And the deliberately playful piano part in »Ausklang« [Concluding Sound] (1984/85) for piano with orchestra, defined by rapid repeated notes, glissandi, chromatic runs and arpeggios, consistently calls to mind the virtuosity of great symphonic piano concertos of the preceding centuries (whereby the repeated notes are an allusion to the American pianist Charlemagne Palestine). The result is a work which explores the area of tension between strangeness and familiarity. Its core musical concept: to outwit the inescapable »Ausklang« of the piano – using various stopping, pedal, resonance, echo and grasping techniques, which prolong the sound beyond its natural limit and let it continue sounding in the orchestra.

Success of the century

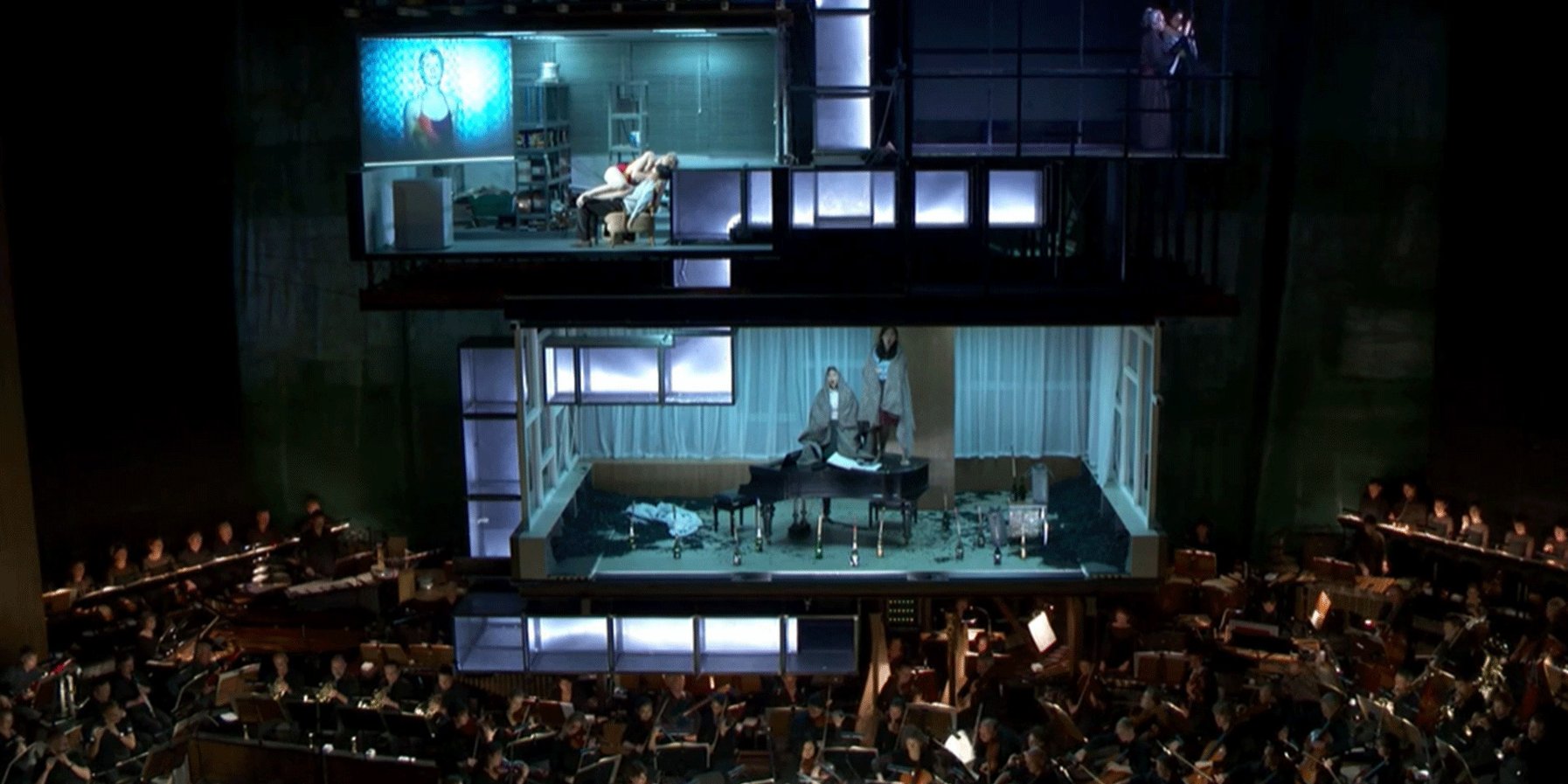

Towards the end of the 20th century, late recognition comes for Lachenmann, who had been met with fierce hostility for decades. In 1997, the premiere of his first and so far only opera, »Das Mädchen mit den Schwefelhölzern« [The Little Match Girl], in Hamburg unexpectedly becomes a great success. All the performances are sold out, a modern classic is born. The composer, here, tells the sad tale of a little girl who on the night of New Year’s Eve is to sell matches and freezes to death – in order essentially to denounce the social coldness in a society which is ruthlessly only preoccupied with itself. The fact that the world is numbed, frozen stiff and really tough, which Lachenmann depicts in his opera, can be heard in the clicking and clanging which the instruments produce, their soft hissing and the brittle sound effects. And we also hear what it does to someone when they are exposed to it: the shuddering and shivering of voices, their faltering breath, their gasping, which make one literally feel the cold.

»Das Mädchen mit den Schwefelhölzern« at the Deutsche Oper

Any goose-pimple-generating, rhythmic brushing sounds on drumheads, which accentuate the hopelessness at the end of the opera, also reverberate in lots of variations in »Schreiben« [literally ‘Writing’ composed of ‘Schrei’, shout, and ‘reiben’, to rub] for orchestra (2003/04). It is as if Lachenmann is once again interrogating his own musical language in this work – as if it has also meanwhile become a tradition, which must be critically re-examined. This principle can be seen even more clearly in »Concertini« for ensemble (2005). Here, Lachenmann seems to »be giving a concert« with himself: fragments from earlier works, such as »Souvenir« (1959), »Schwankungen am Rand« (1974/75) and »Mouvement (– vor der Erstarrung)« [Movement (– before Paralysis)] (1983/84), enter a complex dialogue whereby his String Quartet No. 3, »Grido«, Italian for ‘shout’, (2000/01), comes most clearly to the surface.

Helmut Lachenmann’s »Grido«

»Grido« excerpt in Helmut Lachenmann’s »Concertini«

»The purpose of music is to listen.«

Helmut Lachenmann

Full of surprises

And even at over 80, Lachenmann is still good for a surprise. With »Marche fatale« (2016/17), he writes a cheerful, almost melodious march – and thereby just staggers those who had elevated his style to the status of dogma. Suddenly, his music becomes a scandal, not because it sounds weird, but so unashamedly catchy.

About his late works, Lachenmann says they are the attempt »not to push forward into the unknown, but into the known.« Each work is for him a journey of discovery, a new adventure – after each piece, he wishes to be something different than before. The only constant in all the transformation remains his fundamental conviction: »Der Gegestand vo der Musig isch des Horä« [The purpose of music is to listen], as he emphasises in his Swabian manner of speaking – a route which he had to find all by himself through the dense labyrinth of music, full of countless turnings. Because: » Composing is like dying: you are actually completely alone!« The crucial difference is, however, in art: here, you can be reborn time and again.

- Elbphilharmonie Kleiner Saal

Helmut Lachenmann: The String Quartets

Quatuor Diotima / Ensemble Resonanz

Past Concert - Elbphilharmonie Großer Saal

Ensemble Modern / Sylvain Cambreling

Chin: Graffiti / Lachenmann: Concertini – NDR das neue werk

Past Concert - Elbphilharmonie Großer Saal

SWR Symphonieorchester / Jean-Frédéric Neuburger / François-Xavier Roth

Lachenmann: Ausklang / Beethoven: Symphony No. 7

Past Concert