In the early 1960s, when the whole world was infatuated with the idea of progress, composer Ligeti gave a talk about the future of music to an illustrious audience of academics, politicians and business people. Ten minutes were earmarked for his talk, and he used them to say – not a single word. At the time this was something of a scandal: angry protests were shouted from the audience, and after eight minutes of silence Ligeti was pushed off the lectern.

Looking back now, Ligeti’s little stunt seems to be more of an anecdote. An anecdote, though, that says a lot about him: a sensuous but thoughtful artist, who found the perfect form to express a compelling idea, and an honest intellectual who could speak knowledgeably and eloquently about the most complex issues of composition theory, philosophy, physics and maths. But he could also remain silent when he knew that he knew nothing and that there was nothing he could know.

This an extract from the »Lust am Spiel« (A Love of Games) article from the Elbphilharmonie Magazine (02/2019), which appears three times a year. Order the current issue.

A Blind Man in a Maze

This anecdote also attests to something else, namely Ligeti’s perpetual openness: he refused to commit himself even as regards his own musical future. »I always attempt to try out new things,« he once said many years later. »I’m like a blind man in a maze, groping around, discovering one new entrance after another and finding himself in rooms which he didn’t even know existed. And then he does something. And he has no idea what the next step will be.«

A diverse oeuvre

»I’m like a blind man in a maze, groping around and finding himself in rooms which he didn’t even know existed.«

György Ligeti

It comes as no surprise that Ligeti can hardly be pigeonholed in terms of style. His oeuvre is far too diverse, his expressive resources too varied, and the viewpoints from which he looked at music and the questions that then posed themselves differ greatly from each other. By the same token, his interest in the world beyond music was too wide-ranging – the world which supplied inspiration for his work time and again.

What is beautiful and quite special is that in each of the 100-plus compositions that he recognised at the end of his life, Ligeti always remained true to himself and his artistic identity. And in the literal sense of the word: identity is what stays the same when things or circumstances change.

Feeling of Danger

György Ligeti had about as much to say about personal matters and his private life as about the future of music. Born in 1923 to Hungarian Jews in Transylvania, at that time part of Romania, the 18-year-old Ligeti was barred from studying physics because of his Jewish background, and it was this that led him to the conservatoire in Cluj-Napoca to study music. His father and brother both died in a concentration camp, while his mother survived Auschwitz. Ligeti himself had to do forced labour in the fascist Hungarian army in 1944; he was taken prisoner by the Soviets and managed to escape from the prisoner of war camp during an air raid.

Folk Music as a Bolthole

After the end of the war, Ligeti continued to study music in Budapest, and worked in the field, researching into Romanian folk music. His fascination with the genre had already been aroused by an early encounter with the music of Béla Bartók. After the communists seized power in 1948, folk music offered him a chance to resist the repressive political system: whereas all contemporary music from Debussy onwards was banned, folk music was accepted by the ideology of socialist realism. Therefore, Ligeti composed pseudo-folk music, some of which actually got past the censor. Most of these pieces, however, were banned because they displayed »adolescent rebelliousness« or contained »too much dissonance«.

After the failed national uprising of 1956, Ligeti again managed to flee from the increasing restrictions on intellectual freedom in communist Hungary – this time on foot, crossing the border into Austria. And in his new surroundings, he pounced on everything that he had not been allowed to explore back home: the banned works of Bartók and Igor Stravinsky, and the »even more strictly banned« music of the Second Viennese School led by Arnold Schönberg.

In one of the last interviews he gave before his death in 2006, Ligeti was asked to what extent his younger years with their many sources of danger had influenced his music. His answer was terse: »Under the Nazis and the communists my life was full of risks. That wasn't important to me, but that's how I lived.« He didn't volunteer any further details, simply hinting that, »The feeling of danger is still there.« And yes, it was reflected in the radical nature of his art.

Uncompromisingly Individual

Ligeti was a radical artist first and foremost in his uncompromising individualism, with which he set himself apart from all aesthetic fashions and schools of music as long as he lived. He loathed every kind of dogmatism and absolutism. Thus, his explanation of the distance he kept from the post-war avant-garde with its unyielding insistence on its own standpoints, as if there could be no alternative.

It wasn't long after his arrival in the West before he was in touch with the leading representatives of contemporary music, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Pierre Boulez and Luigi Nono. These contacts were friendly and a source of mutual inspiration. However, he never really became integrated into their circle: he was critical of the serial composition technique favoured by the Darmstadt School, which he felt was too theoretical, too structural in concept, leading in the final event to music that was faceless and interchangeable.

»Under the Nazis and the communists my life was full of risks. That was not important to me, but that is how I lived.«

György Ligeti

the hypnotic impression of standstill

Ligeti was working on his own alternative to the traditional functional harmonics, and the solution he arrived at was utterly new: music with such density in the individual parts (»micropolyphony«) that it becomes impossible to distinguish melody, harmony and rhythm. Tone colour and dynamics alone determine the path the music takes, while the individual parts with their events in small sections cannot be distinguished from one another, blending into a continual overall sound that is constantly altering, moving through space, and may even arouse the hypnotic impression of standstill.

Ligeti: Atmosphères

»I am an anti-ideological person. I do not want to be harnessed for some purpose, not by an ideology and not by any group.«

György Ligeti

Sound Textures

This technique was soon being referred to as »Klangflächenkomposition« (sound texture composition«. Ligeti used it for a full orchestra (»Atmosphères«, 1961), for the organ (»Volumina«, 1962) and for human voices (»Requiem«, 1965) – and he enjoyed overwhelming success with it. When Stanley Kubrick then used extracts from the »Requiem« and from »Atmosphères« in his 1968 film »2001: A Space Odyssey«, Ligeti's music reached such a wide audience that even German TV magazine »Hörzu« printed a one-page portrait of the composer. (However, he had to sue to get any royalties for the soundtrack, which used his music without his knowledge.)

Garish, Teeming, Grotesque

In these early works, the rare qualities of Ligeti's music were already evident that characterise all his compositions: the love of games and complexity, structural clarity, stupendous virtuosity, intellectual acuity, freethinking, a delight in experiment, wit and – perhaps most important of all – accessibility. Unlike so many other post-war avant-garde composers, Ligeti was not afraid to write sensuous music.

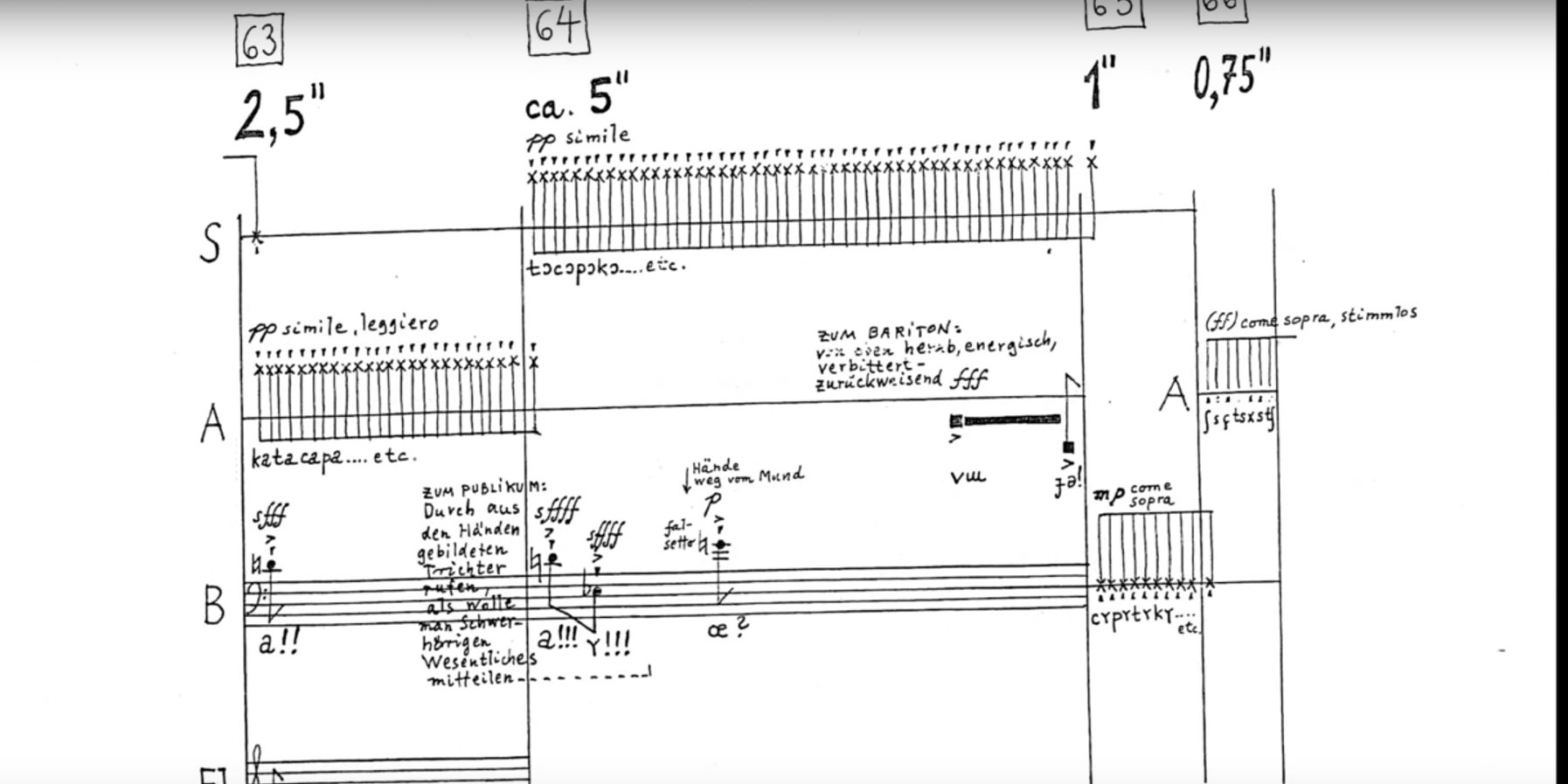

And that remained the case even after he felt he had exhausted the potential of sound texture composition. Ligeti now turned his attention to phonetic experiments: for the highly virtuoso mimodramas »Aventures / Nouvelles Aventures« (1962-65), he created an imaginary nonsense language out of articulated sounds and modulations.

Anti-Anti-Opera

But Ligeti had the most fun of all, with the most opulent grotesquery and the most biting irony in his entire oeuvre, in his only opera: »Le Grand Macabre« is set in the apocalyptic surroundings of the fictional city Breughelland, populated by bizarre, decadent characters, hopeless losers who somehow retain a positive approach to life. Nothing works here, not even the end of the world that has been announced for midnight. The end of the world sinks into a swamp of boozing, sex and blustering, and life goes on as before.

In reference to Pierre Boulez’s fiery call for an »anti-opera« (»Blow up the opera houses!«), Ligeti called his work an »anti-anti-opera«, making use within the traditional framework of the format of all his considerable musical repertoire: sound textures, serial structures, elements of animated film music and the now legendary prelude of a chorus of jarring car horns make »Le Grand Macabre« a garish revue teeming with human madness.

Read about how Ligeti found his way out of a deep creative crisis, and what connects him with Kafka, the Aka people of Africa and research into the chaos theory, in the Elbphilharmonie Magazine (issue 02/2019, in German only).

Text: Carsten Fastner, last updated: 18 Apr 2019