Text: Renske Steen, 20.09.2024

Translation: Robert William Smales

Some songs are so good that they are just crying out to be covered. Those absolute masterpieces that no one can plan. And that open up so much more scope for performance and inspiration that other artists just cannot keep their hands off them. There are bands out there that have turned it into a business model, and shows where only covers are permitted. Sometimes a cover ends up becoming even more famous than the original. »Nothing compares 2 u« was originally sung by Prince and not by Sinead O’Connor. Another example is »Valerie«, one of Amy Winehouse’s hits, which was in fact a song by the relatively unknown band The Zutons (who are incidentally still around). From 17th-century house music to contemporary pop covers: good music has always been transferred for other line-ups. The producer Mark Ronson had asked Winehouse to do the vocals for the song, which he had planned for his own studio album full of covers. After its huge success, »Valerie« also featured on the seminal album »Back to Black«.

Pianomania 2024/25

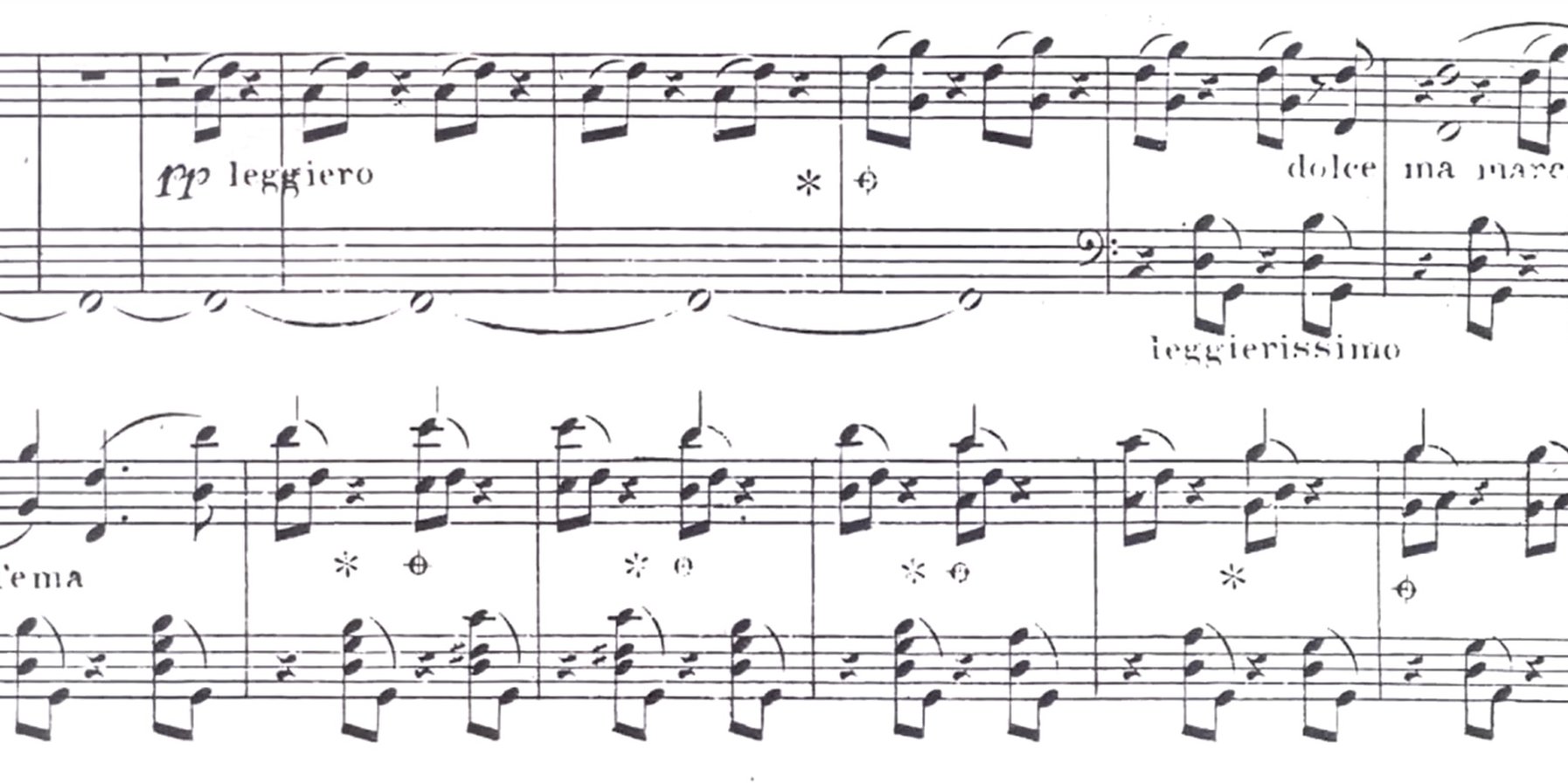

The popular series »Pianomania« has the theme of »Transcriptions« in the 2024/25 season. Young, up-and-coming stars perform arrangements of great orchestral works for piano – with three two-handed pieces and one four-handed work in store.

For other instruments :Spontaneous transcriptions

If music is good, it will be copied – that’s always been the case. It started in the Baroque period, but for different reasons. To begin with, there wasn’t as much music around at the time. Another – much more important – factor was that there were only a limited number of musicians (and even fewer female musicians) who could play live in person. So if a sheet of music with the latest work, perhaps from Telemann’s pen, turned up and there happened to be musicians nearby, they would simply play it on the instruments available. That might be a viola da gamba, a spinet, or perhaps a cornett. This sometimes worked without someone having to re-write the sheet music first for the respective line-up of instruments. More often than not though, someone would take it upon themselves to hurriedly adapt the sheet music beforehand. They often kept their new version to the original. They transcribed – or, in other words, they transferred.

Johann Sebastian Bach also wrote several such transcriptions. The famous Baroque composer most probably created many more than those officially recorded as part of his canon. He transcribed primarily for practical purposes: writing sheet music, enlarging or reducing sets of parts, developing musical ideas in accordance with the strict rules of harmony, adapting his own or other people’s work for instruments that happened to be to hand. He didn’t see this practice as reprehensible, and he didn’t see it as steeling feathers from other people’s caps either. Instead, he regarded it as part of his work as a composer. All his colleagues did it, but he had most certainly mastered the art of transcription.

For the home :Great art designed for small salons

Transcriptions took a back seat for a few decades, due to the ever-evolving musical landscape, and the more elaborate languages of sound that became faster and faster in tempo. They weren’t of any significance in the professional realm. Instead, orchestral works were transcribed for the home by what we would call hobbyists. Mozart’s work seems to skirt by them almost entirely, for example, and Beethoven dismissed transcriptions as unnecessary.

But the 19th century then saw the growing bourgeoisie develop a veritable piano mania. There was hardly a single household in these bourgeois circles that did not own a piano. It served as entertainment and a status symbol all at the same time. Salons were transformed into small concert halls. This boom led to a rapid rise in demand for arrangements. Many people were keen to enjoy the most popular concerts and operas in the comfort of their own four walls – and this became a new, lucrative source of income for composers. It meant that they were in a position to share their art with many more people through piano reductions of their large-scale works, in an era long before the invention of the radio, records or streaming services.

For virtuosos :Franz Liszt’s piano transcriptions

Franz Liszt was one of the first composers to fully exploit the possibilities that transcription opened up. He saw a potential that went far beyond Bach’s approach, namely in »virtuosification«. Liszt proceeded in a way that knew no limits and accepted no boundaries. He stopped at nothing, whether it was Beethoven symphonies, Schubert songs or Wagner operas. He even reduced Hector Berlioz’s »Symphonie fantastique«, which is almost impossible for a full, huge orchestra to play, down to ten fingers on piano. A work not suitable for the average hobby pianist, but rather intended for genius aficionados (like Vadym Kholodenko, who performs this insane work in the Recital Hall on 18 January 2025)

Berlioz/Liszt: Symphonie fantastique

Run-of-the-mill Biedermeier amateur musicians steered clear of such works. But there was still a wealth of symphonies, concertos and songs that were re-written with painstaking attention to detail and dedication by countless amateur transcribers for their own range of instruments. Whether they were always flawless transcriptions in the spirit of Busoni, or arrangements with more room for creative interpretation is secondary in importance. The main thing was they were fun.

The Bach fan Busoni :A new category of transcriptions

Ferruccio Busoni opened the floodgates to the big, wide cosmos of transcriptions. His most famous work is arguably his transcription of Bach’s Chaconne in D minor (originally for solo violin) for piano. As well as being an advocate of transcriptions, Busoni was also a fan of Bach. His father was responsible for imbuing this enthusiasm, having put works by the composer on his desk on repeated occasions. It should be remembered that, despite a small renaissance in interest in Bach a few decades earlier, the composer was far less popular at the time than, say, Carl Czerny.

Hélène Grimaud plays Busoni’s transcription of Bach’s Chaconne

Transcribing Bach works allowed Ferruccio Busoni to gradually find his own musical and aesthetic path. He left showmanship behind and made no effort pretending that a piano could be everything. Instead, he became increasingly serious and consistent in his sound language, distancing himself more and more from the thinking of Franz Liszt. As a result, he created a category all of his own for transcriptions.

Previews on the piano :Piano versions of great orchestral works

Others still kept on transcribing – including those less interested solely in writing effective piano music, and not looking to re-write an entire music theory treatise on transcriptions! They wrote transcriptions for a different reason: because the original work for orchestra was not published (or could not be published).

Even before the famously scandalous premier of Igor Stravinsky’s »Le sacre du printemps« in Paris in 1913, the composer had published a version for piano for four hands, for instance. A masterstroke of deception! He had transferred all the colours and timbres of the huge orchestra to the keys – without missing out anything. He played it with his mentor Claude Debussy to a small gathered audience, and this version of the work remained the only available version for a long time, since the orchestral score was only published years later, after the premiere was deemed a failure. One advantage of this piano version was certainly that Stravinsky was able to play, perform and present his work himself, without being reliant on orchestral patrons and critics.

Lucas & Arthur Jussen play »Le sacre du printemps«

Maurice Ravel had a similar experience when he made a transcription for solo piano of his work »La Valse«, originally planned as a ballet, shortly after its premiere. He tried wherever possible to stage the orchestral arrangement in all its complexity. And wherever this wasn’t possible, he would add an additional part separately.

Fortunately for us, Ravel also created a version for two pianos, which is performed more often today than the original. The transcription by Lucien Garban, a colleague and friend of Ravel, also for two pianos, was not as successful. It seems that producing a bad copy is not the solution either.