Die Variation :Ein altes musikalisches Prinzip

»A lot of words and little sense« – thus the disparaging comment of French music theorist Jérôme-Joseph de Momigny 200 years ago on the subject of the musical variation. Pretty astonishing if we consider the role that cycles like Bach's famous »Goldberg Variations« play in today's concert repertoire. Moreover, the variation is one of the oldest of all musical forms: its beginnings in art music go back at least as far as the vocal works of the late Middle Ages.

The term itself has been used with the meaning now customary since the very early 17th century. It is derived from the Latin »variatio«, which simply means »alteration«. In other words, an existing work – at the outset, it was generally a song or a chorale – is altered, or varied. Then, in the 18th century, the variation emerged as a musical genre in its own right: a cycle consisting of a theme followed by a set of variations on that theme.

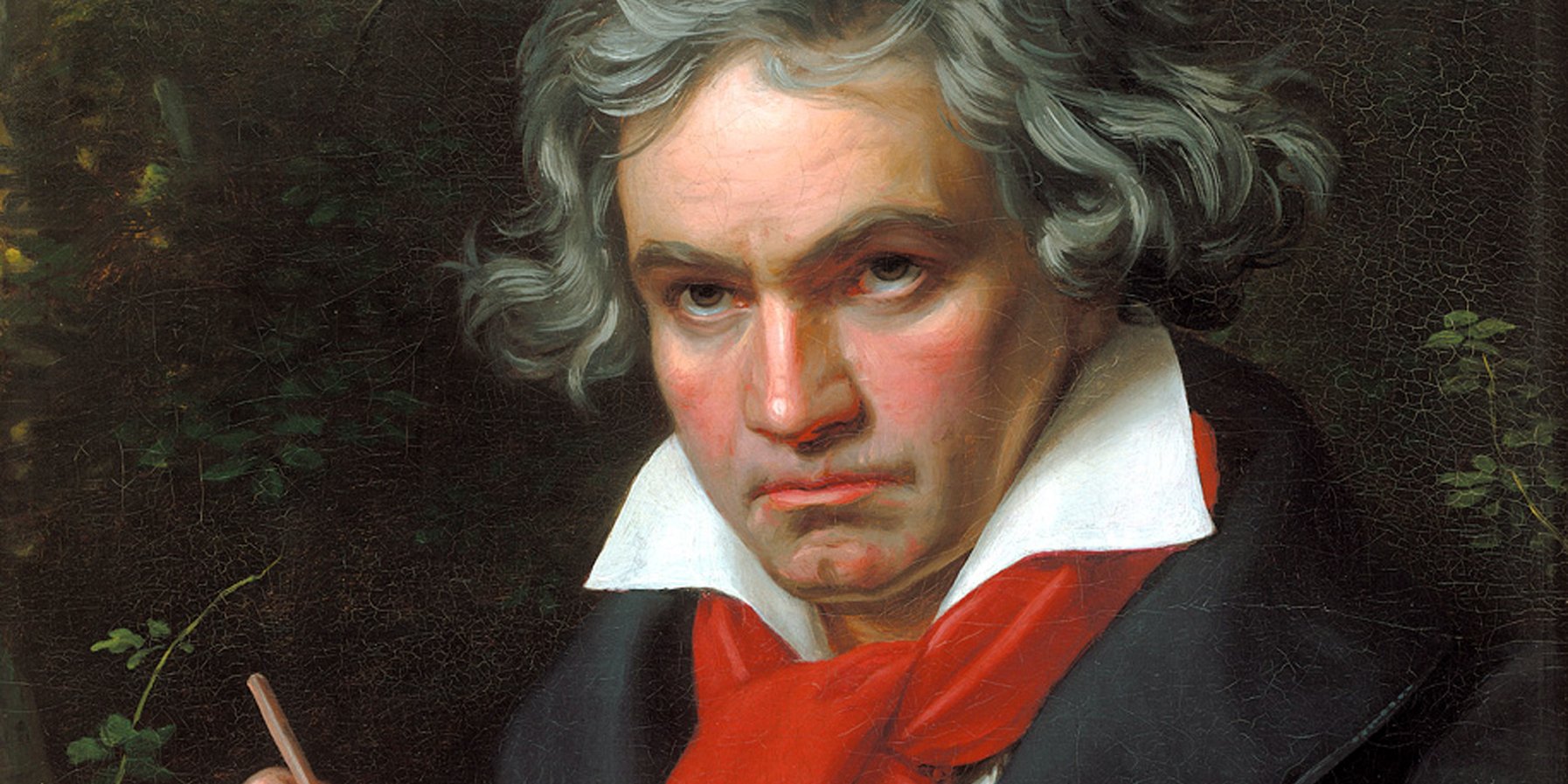

Beethoven sets new standards

Variations were functional music at first, designed to entertain. But this changed at the latest with Beethoven's big cycles of variations, which set new standards in terms of creativity and pianistic brilliance. These works established the cycle of variations as a fixed and unchangeable form where the theme of the introduction undergoes a logically consistent development. The theme itself had to be significant enough to be recognised at any point in the variations. Musicologist Adolf Bernhard Marx went as far as to describe a set of variations as an expression of different »emotional states« of the theme. It was not long before this principle, originally applied to compositions for keyboard instruments, was transferred to the orchestra as well: mention can be made of Brahms's »Haydn Variations«, to cite one example.

»A portrait of the entire world of music« :Beethoven's »Diabelli Variations«

»Beethoven reflects on original and thoroughly humorous music from the past, while at the same time pointing to the future.«

Among the best-known contributions to the genre are Beethoven's »Diabelli Variations«, at the same time one of the most complex and difficult of all piano works. The great pianist Alfred Brendel, for instance, described them as alternating, full of contrast, between »earnest and lyricism, mystery and depression, aloofness and obsessive virtuosity« - a good illustration of the theory of different emotional states. In his variations, Beethoven reflects on the one hand on original and sometimes thoroughly humorous music from the past, while at the same time pointing to the future with bold and experimental sounds.

Nicht eine, sondern 33 Variationen

The history of the cycle's composition is likewise of interest: in 1819 Viennese music publisher and composer Anton Diabelli asked a number of composers to write one variation each on a waltz theme he had written, which he then planned to publish as a collection. No fewer than 51 composers submitted a contribution, among them Franz Schubert, Mozart's son Franz Xaver, Johann Nepomuk Hummel and the 11-year-old Franz Liszt.

But Beethoven wasn't content to write just one variation. He wrote a total of »33 alterations«, in which he »comments on, criticises, improves on, parodies, ridicules, reduces to absurdity, disregards, enchants, refines, laments, cries over, tramples on and finally transfigures with humour« the rather banal theme, as Alfred Brendel wonderfully summarizes.

So klingt Beethovens Variation Nr. 1

Composed interpretation :The composer Hans Zender

Hans Zender raised the variation principle to a new and completely different level. Born in Wiesbaden in 1936, he died in October 2019. Zender's name should be familiar to older Hamburg music lovers in particular: from 1984 to 1987 he was Director of Music at the Hamburg State Opera, a predecessor of Kent Nagano. But in addition to his work as a conductor, he also made a name for himself as a composer, and in this capacity he invented a new genre single-handedly: the »composed interpretation«. On the one hand this is an instrumental arrangement of an existing work for ensemble or orchestra, but on the other it also constitutes a reinterpretation. In 1993 Zender already applied this principle with immense success to Schubert's »Winterreise«, which he arranged for orchestra.

Und so klingt Zenders Variation Nr. 1

»The very first variation is deconstructed with glorious eccentricity, including the sound of bells. (…) After listening to these Diabelli Variations, one will undoubtedly hear the original with completely different ears.«

Rondo Magazin

Zauberische Farben

In 2011 the Ensemble Modern of Frankfurt invited Zender to have a go at Beethoven's »Diabelli Variations«, and he responded with a set of »33 Alterations of 33 Alterations«. But the work is no mere arrangement for orchestra; rather, Zender deconstructed the Beethoven variations, adding new material, bathing them in »colours sometimes magical, sometimes garish« (BR-Klassik) and artistically teasing out the special features of the individual movements.

Doing justice to the original, but still introducing something new – Zender said that this challenge was at least as great with the »Diabelli Variations« as with Schubert's »Winterreise«: »It appealed to me to try and pull off this balancing act again. Nietzsche said that the relationship between old and new is always that the new destroys the old. There is only one way to avoid this, and that is to ›float fearlessly‹ over the abyss of history. This ›floating‹ to and fro between familiar styles has its own attraction, and can produce new experiences for both the composer and the listener.«

Text: Simon Chlosta, last updated: 12.05.2020

Cover picture: Sculpture by Ottmar Hörl

In Concert: Beethoven's and Zender's variations in one concert

- Elbphilharmonie Großer Saal

Herbert Schuch / Remix Ensemble: Diabelli-Variationen

»Roll over Beethoven«

Past Concert