Frédéric Chopin: Cannons Under Flowers

Frédéric Chopin’s compositions are among the most frequently-played piano works anywhere in the world. He is revered not only as the master of the miniature, of études, preludes, waltzes, polonaises and mazurkas, but also as a composer who literally expressed the essence of the piano and completely changed piano technique. As a brilliant improviser, Chopin developed his pieces as he played them, and only later put them down on paper.

Chopin: Nocturne in As-Dur op. 32 Nr. 2, Lento

Born near Warsaw in 1810, Chopin died only 39 years later in Paris. For the entirety of his short life, the composer suffered from the division of Poland: Russia, Prussia and Austria had broken up the noble republic in the 19th century and divided it up amongst themselves. The young Chopin was a patriot, but he failed to gain a foothold with his music in his native city, which prompted him to emigrate: first to Vienna, and thence to Paris, where his father originally came from. In the French capital he received a warm welcome, not least from many other Polish emigrés who saw his music as the epitome of their yearning for home.

Loved But Misunderstood

Although he adored opera, Chopin wrote almost solely for the piano. He took inspiration from Polish folk dances, as well as from Italian opera and from old masters such as Johann Sebastian Bach. Something that sets him apart from many other great composers is the widespread popularity of his music during his own lifetime – a popularity that holds to this day. The other side of this coin is that Chopin's music was often well and truly misunderstood, with many seeing him as a salon dandy and melancholy dreamer. Robert Schumann, on the other hand, understood his fellow composer: »Chopin's works are cannons sunk beneath flowers«.

Stanisław Moniuszko: In Resistance

He wrote the most important Polish opera, yet he remains as good as unknown outside Poland: Stanisław Moniuszko. His stage work »Halka« took Russian-occupied Warsaw by storm in 1858. The story is about a peasant lass who falls in love with a bachelor of noble blood. He promises to marry her, but ends up leaving her when he finds a bride from his own class. Moniuszko's rousing, emotional score left the audience in no doubt as to his mission: this was an appeal for resistance – against the class society and against the Russian occupying forces. The 29-year-old composer mirrored the feelings of a people that had benen oppressed for decades.

Moniuszko: Halka

Moniuszko's revolution opera met with thunderous applause, and became a musical symbol of the Polish liberation movement: the first national Polish opera was born. However, another 60 years were to pass before Poland managed to shake off the foreign yoke. Finally, the end of the First World War saw the foundation of the »Second Republic«, and the country regained its sovereignty.

Moniuszko remained a celebrated composer at home, but he was unable to establish himself on the international scene: his patriotic operas were too strongly geared to the political situation in Poland, which aroused little interest abroad.

Karol Szymanowski: The Cosmopolitan

Polish independence only lasted for twenty years after the First World War: in 1939, the country was invaded by Nazi Germany. The most influential composer of this period was Karol Szymanowski. Unlike Moniuszko, he managed to combine the folk music of his native Poland with modern influences from the West and Russia: the resulting synthesis was quite new, and met with a positive response abroad, too.

Born on an estate in the Ukraine that had formerly belonged to Polish nobility, Szymanowski had visited Italy and Vienna before the war. There he not only got to know the provocative, rhythmically complex music of Igor Stravinsky, but also Impressionist compositions from France – music that tries to capture the mood of the moment in timbres and layers of sound.

Szymanowski: Violinkonzert Nr. 1

When Poland became a free state again in 1919, Szymanowski took up residence in his native land for the first time. He now forged the impressions from his travels into an idiosyncratic musical style between East and West, between modernism and folk music. Evidence of this is found in two operas and four symphonies from his pen, as well as violin concertos, chamber music and songs.

Witold Lutosławski: the world of our dreams

»It seems to me that music should convey something of the world of our dreams, of an ideal world that we long for.« Witold Lutosławski knew what he was talking about. Born in Warsaw in 1913, the composer grew up and lived for many years in a world which was anything but ideal for an aspiring young artist. He struggled to develop as a musician first under the Nazis, then later under Soviet rule.

Lutosławski was a child prodigy, beginning to play the piano at a very young age and taking his first tentative steps as a composer aged nine. 1939 saw the Nazi invasion of Poland and Lutosławski fell into German captivity, but he managed to escape after eight days. Back in his occupied home city, he eked out a living as a café pianist. In 1944 the Warsaw resistance fell apart and just a few days later, the city lay in ruins. Nearly all the young composer's manuscripts were lost in the fire.

The devastating war years were followed by Soviet rule, impregnated by Stalin's rigorous ideology. »Socialist realism« was the official doctrine of the arts, which suppressed all abstract and avant-garde art, everything that was critical of the establishment. This affected Lutosławski's First Symphony, his first major work, which the Party stigmatised as »formalistic«, banning its performance. The composer had no other choice but to keep his head above water with occasional compositions. Only after Stalin's death did Lutosławski find his way to his own personal musical style.

Lutosławski: Symphony No. 3

His works teem with unconventional structures and surprises, with wit and terror rubbing shoulders. Lutosławski combines this with playful elements, with »controlled coincidence«, as he once called it. And in the midst of it all, we find moments of immense sensuousness. »Lutoslawski was fond of saying«, the composer Krzysztof Meyer recalls, »that the utmost goal of science was truth, while the utmost goal of art was beauty«.

»Lutosławski's music is of such depth and beauty that it literally takes your breath away.«

Anne-Sophie Mutter, Geigerin

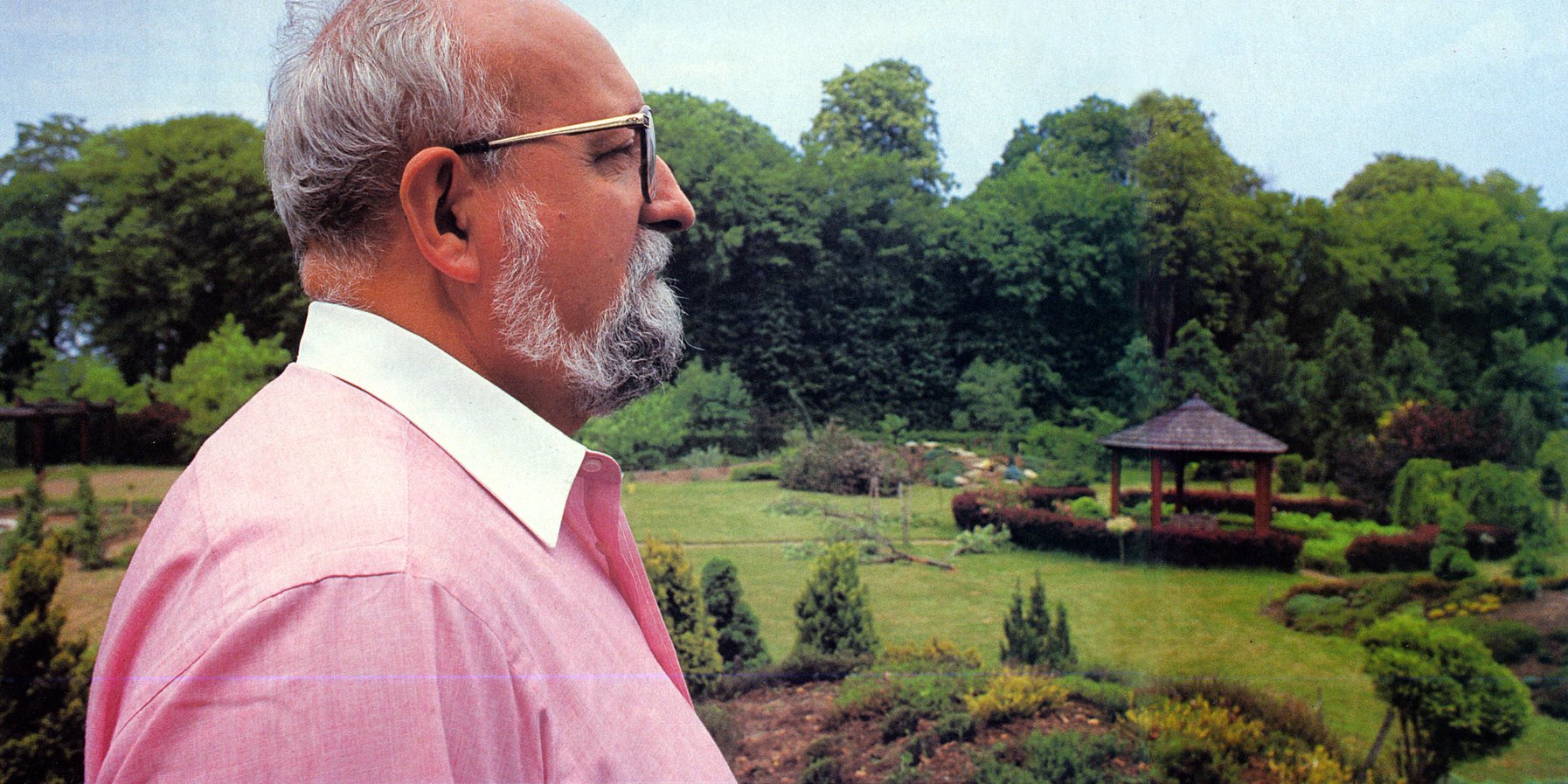

Krzysztof Penderecki: Querkopf der Neuen Musik

Krzysztof Penderecki, born 20 years after Lutosławski, is regarded today as one of the greatest living composers of classical music. Unlike the circumstances his older colleagues had to endure, he found himself in a more hopeful situation in Poland. In the communist People's Republic of Poland, which existed until 1989, he received awards from the state, was head of the Krakau College of Music, and was allowed to travel abroad as a conductor.

But these advantages didn’t stop Penderecki from adopting a musical stance: he provoked the Communist regime not only as a supporter, at the outset of his career, of the frowned-upon composers of New Music in the West, but also as a devout Catholic and composer. He dedicated his work »Lacrimosa« to the Polish uprising of 1970 against the state. Shortly after the first performance in 1980, social unrest broke out – however, nine years had to pass until the Iron Curtain fell.

Penderecki became the best-known maverick in the world of New Music at the latest with the appearance of his »St. Luke Passion«, with which the erstwhile avant-gardist caused a full-blown scandal in 1966. In this work, he declared his support for a musical ideal that was diametrically opposed to that advocated by his revolutionary-minded colleagues. For example, Penderecki had recourse in places to the traditional key system with major and minor that more »progressive« composers now rejected. This powerful score has a direct impact on the senses, it is intuitively understandable and makes no attempts to hide the influence of Romanticism. The ideal Penderecki was aiming for was a mixture of tradition and innovation.

Penderecki: St. Luke Passion

Henceforth ostracised by avant-garde circles, Penderecki won just as many admirers with his volte-face. The controversy came to a head with the piano concerto »Resurrection«, dedicated to the victims of «Nine-Eleven«. The Polish press criticised the work as being permeated by Soviet aesthetics. Penderecki for his part countered with an attack on the Polish music scene and threatened to emigrate. But in the meantime things have calmed down: Penderecki has stayed in Poland, but remains true to himself.