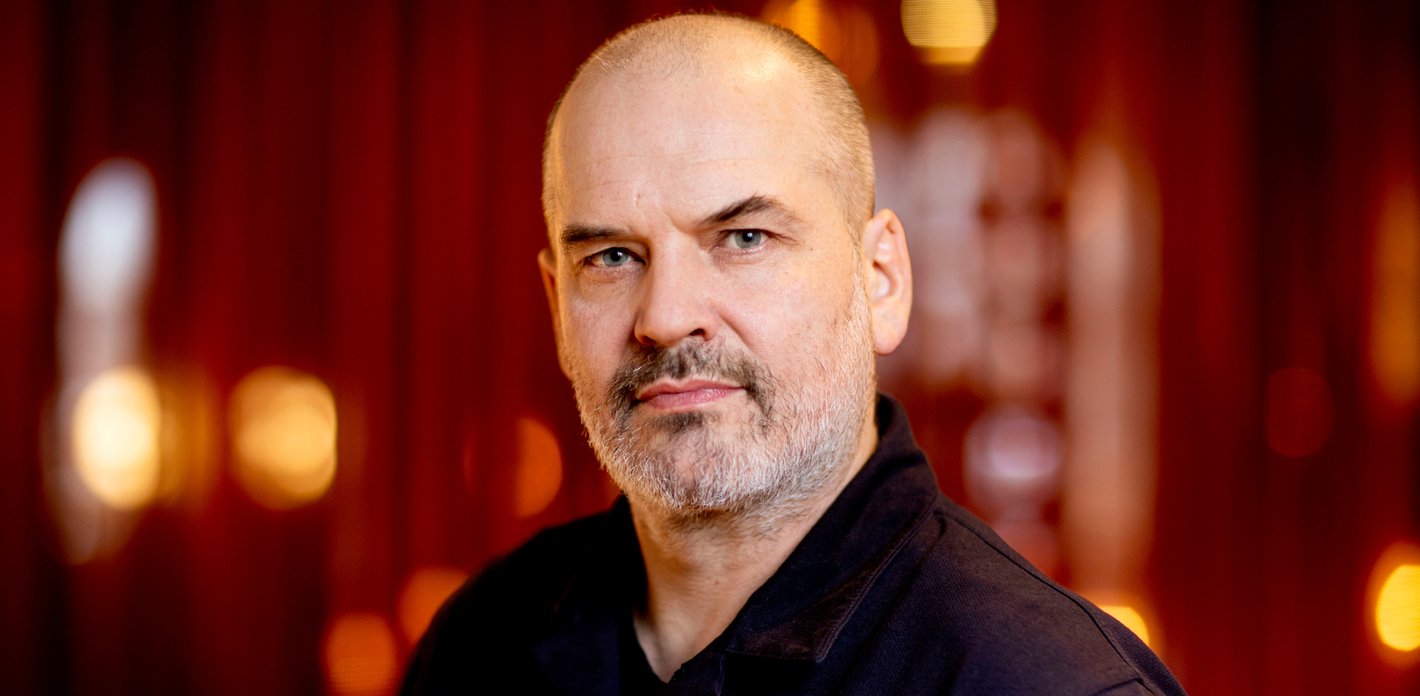

The Austrian bass-baritone Florian Boesch is one of today’s great lieder singers – »an elemental force that grabs people’s attention on stage as if it were a black hole« (Salzburger Nachrichten). In this interview he talks about his accent, about speaking in singing and the attraction of his residency at the Elbphilharmonie.

»The essence of lied singing: to be nowhere but in the here-and-now« :Florian Boesch in conversation with Bjørn Woll

Mr Boesch, are you an early riser? As a rule, artists suggest a much later time of day for an interview, and singers in particular often prefer not to talk in the morning, as we are doing now.

Florian Boesch: That’s an interesting and highly topical issue as a result of the underemployment caused by the pandemic. I actually thought I was a night person, but last year I found myself getting up more and more at sunrise. I enjoyed that a lot, but in the long run it’s not compatible with my job. When I go back to singing between 70 and 100 evenings a year, I’ll obviously be getting up later. Then there’s the age factor: I turned 50 in May (2021), and these days I can’t sleep as long as I’d like to any more. So the bottom line is that I’m turning into an early riser, which will be a problem for a while because of my profession.

I must admit that I was a bit apprehensive before our meeting: you once said in an interview that journalists often ask you boring questions.

I know – I’ve regretted saying that ever since! But my time is precious, and so is yours. And I don’t find it so constructive when people ask me the same questions time after time. Personally, I welcome it if a journalist breaks out of his routine just a little and tries to find a new angle. I’ve certainly been having more interesting interviews since I made that comment. (Laughs.)

Then I hope you’ll find the next question interesting as well: As an Austrian you speak German with an accent, and that has an influence on your articulation and on the colouring of the vowels. Is that an advantage for a singer, or a drawback?

Definitely an advantage! The individual colouring of language is an absolute bonus because it latches on to the naturalness of speech. If I hear a singer forcing an articulation on himself that has nothing to do with the articulation he grew up with, that is already artificial in my opinion. Now that doesn’t mean that it would make sense for me to sing Goethe, Heine or Eichendorff in my regional accent or even dialect. But a hint of local colour with its specific sound can be used in the right dosage to improve the quality of the singing, to make it sound more natural.

»When I have given a good lieder recital, I walk off stage and say to myself: I’ve been speaking.«

-

About Florian Boesch

His father Christian was an opera singer, while his grandmother Ruthilde was a chamber singer and his first singing teacher. Nonetheless, Florian Boesch was a true late starter: he didn’t begin studying voice until he was 27, after he had previously been a student of design and sculpture in Vienna. Significant musical influences were the bass-baritone Robert Holl, a student of the legendary Hans Hotter, and, even more important, the conductor Nikolaus Harnoncourt: »14 years, hundreds of concerts! Harnoncourt was the most formative influence in my musical career«.

Boesch rarely appears on the opera stage, and when he does, he prefers to work with producer Claus Guth at the Theater an der Wien, which has become his regular opera house. But the singer, who is now (in 2021) 50, feels most at home giving song recitals in the world’s leading concert halls and at major festivals like the Salzburg Festival. His partner at the piano is mostly either Malcolm Martineau or Roger Vignoles, both of whom he has been working with for many years. Another concert format he is fond of is a song recital put on together with the ensemble Franui as music theatre with masks. This intensive exchange with artist friends and colleagues plays a central role in Florian Boesch’s understanding of music. In 2015 he was appointed professor for lieder and oratorio at the Vienna University of Music, enabling him to pass his own knowledge on to the younger generation.

Talking of sounding natural: classical vocal music is probably the most artificial form of expression there is. Particularly among lieder singers there are artists like Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau or today’s Christian Gerhaher who tend to emphasise the artificial side of the genre. And then there are singers such as Holger Falk or Johannes Martin Kränzle whose performances sound less affected, who have a natural narrative flow. Do you agree? And which camp do you feel you belong to?

I entirely agree with your assessment and the order you state the names in. If I look at these two ›schools‹ of interpretation, one goes back to Fischer-Dieskau and the other to Hans Hotter. My singing ideal is a natural rendering akin to speech. When I have given a good lieder recital, I walk off stage and say to myself: I’ve been speaking. And I mean that to apply to both the articulation and the singing. My aim is to develop a natural expression of personal commitment in my singing. But you’re right of course, singing is a priori the most artificial form of expression. On the other hand, this also has one clear advantage.

Namely?

Because classical singing is in itself artificial, the singer is never confronted with the difficult task of pretending his performance is genuine. This particular point is quite different in theatre: when an actor whispers on stage in Vienna’s Burgtheater, it’s truly absurd – the huge stage means that the whisper has to be loud and strained, otherwise the audience won’t understand it. So theatre acting claims to be realistic, placing it at loggerheads with the discipline. We singers don’t have this problem as our articulation is artificial per se. That important distinction lifts things on to a completely different level, enabling us to build something that is entirely new.

So if this is impossible by definition, how do you as a singer still manage to achieve a rendering that appears natural?

Let me quote Heinrich Heine’s poem »Es leuchtet meine Liebe«, which Schumann set to music. In one line Heine says »Wenn ich begraben werde, dann ist das Märchen aus.« – »When I am buried, the fairy tale is over.« What he means is: I have nothing to tell the world except for what I have direct access to, namely myself. I can only talk about myself. And that’s why the stories I tell always feature an element of commitment. I see myself as a committed professional, and for me this view of my work is clearly linked to the meaning of what I do for the audience and for society at large. I go on stage to express my personal commitment and to say to the audience: at least for a little while, you are not totally alone, even if you cannot express your commitment because our society has struck this from the agenda of everyday life.

Are you so fond of song recitals because they are so small and intimate, so quiet and personal? In other words, everything that happens less and less in today’s society, at least in the public arena.

I am a text singer, I sing texts. Always! When Schubert wrote a song, he had a text in front of him that inspired his music. With the exception of »Wozzeck« and a few examples by Hofmannsthal or Oscar Wilde, I don’t know a single opera libretto that comes even close to five lines of verse by Heine, Goethe or Eichendorff. Not one! Not even Mozart’s acclaimed Da Ponte operas. I can scarcely bear to listen to them any more – there’s not a line in them that really touches me. That’s why I have so little interest in opera as an art form.

»I sing differently every evening!«

Then let’s stick to song recitals, and talk about the pianists you work with. During your residency at the Elbphilharmonie you appear alongside different pianists, with Alexander Lonquich and your longstanding piano partner Malcolm Martineau. What influence does the pianist have on your singing? Do you sing differently with different pianists?

I sing differently every evening! I am not an artist who rehearses a lot, which is why I value a long-term piano partner – I’ve been appearing together with Malcolm Martineau for almost 20 years now. I don’t rehearse in search of the right form in order to then reproduce it. It’s the moment that interests me, and here permeability plays an important role – you’ve got to be open to that, otherwise you can’t feel the moment at all.

I work with repertoire that speaks to me, that moves me or upsets me, and my singing reflects these emotions. Emotions that change from one day to the next. I must have sung Schubert’s »Winterreise« a good 50 times by now, and every time I found myself in a place where I hadn’t been before, a passage that I experienced quite differently. That’s what makes singing so exciting for me: I don’t want to know anything about it, I want to discover something new about it. That in turn means that what the pianist plays is incredibly important: I don’t know what to expect in advance, and I need to respond on the spur of the moment. That constitutes the essence of lied singing – to be utterly present, to be nowhere but in the here-and-now.

Is it an advantage that your status as artist in residence at the Elbphilharmonie in the 2021/22 season gives you the opportunity to programme several recitals instead of just one, as is usual for guest artists?

Let me name the most obvious example: I’m a great fan of Ernst Krenek’s »Reisebuch aus den österreichischen Alpen«, which I regard as one of one of the most important song cycles ever written, and definitely in the 20th century. But people still furrow their brow in apprehension when they see Krenek’s name on the programme, as it reminds them of the atonal music he wrote in his late era. But the »Reisebuch«, which dates from 1929, shows that the composer still managed to evolve a style that was tonal and individual, even within the terms of the Schönberg doctrine. Whenever I have a residency, I want to perform this cycle. And if I frame it with Haydn’s »Seasons« for example, or Schumann’s »Das Paradies und die Peri« with Simon Rattle, then it’s easier to sell.

As part of your residency you are also singing Bach cantatas with Il Pomo d’Oro, an ensemble that follows historic performing practice. Does it make a difference to you whether your singing is accompanied by a traditional orchestra or a period-performance one?

Not at all. What’s bad news is all these orchestras that think they know better! And I mean all such ensembles, regardless of whether they look back on a long tradition and cultivate a modern sound, or whether their long tradition goes hand-in-hand with historically informed practice. The prequisites for quality, alertness and permeability are simply flexibility, openness and an interest in the present.

In your chamber-music recital with members of the Artemis Quartet and Alexander Lonquich, you juxtapose songs by Schubert and Schumann with their chamber music. And in your longstanding work with Musicbanda Franui, you also place the classic art song in a different context. Does the public sometimes need to be pushed out of its expectation comfort zone? Do we need a change of perspective?

First and foremost, as a lied singer I am a passionate champion of the original form; for me, the classic song recital is perfectly adequate. I’m absolutely not a fan of change for change’s sake. To people who say we need to do something different now and again I say: no we don’t! We don’t need to do something different, we need to do what we’re already doing better. To do it more honestly! To make it more interesting! If I try out different formats, a lot of it has to do with the choice of musical partners. Believe me, creating a song recital together with a group like Musicbanda Franui is an interesting, inspiring, even exciting process. A totally worthwhile experience.

Unlike most of your fellow singers, you are hardly present in the digital world. You seem to reject the social media for the most part – or do we have the wrong impression here?

Instagram is the embodiment of evil! And Facebook is the embodiment of falsehood! I can’t begin to say how frightful I find all this stuff. That is my personal opinion, though I am neither a technology pessimist nor a cultural pessimist. And it goes without saying that my voice students need a digital presentation, which is something I don’t need any more. So even though I don’t want to, I’m forced to look into the subject. But what’s happening in this world of ours in connection with the social media is a huge drama where the big democracies are being manipulated, while individuals are being retrained as obedient consumers. It’s no coincidence that I mentioned Instagram first: it calls out for a fake surface as the most important category of human existence. This represents a »devaluation of life«, as Krenek calls it in his »Reisebuch«: the ultimate »vulgarisation of humanity«.

The interview was conducted by Bjørn Woll. Last updated: 29.7.2021