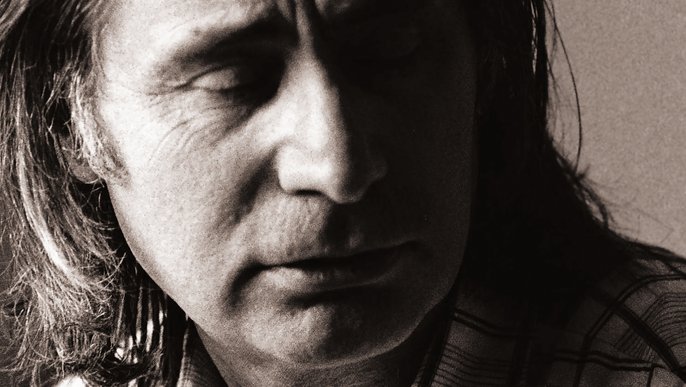

The German-Russian composer Alfred Schnittke is without doubt one of the 20th century’s most important composers. His works have been a regular feature in concert programmes for decades – and his name also regularly comes up in the worlds of film music, music theatre and even ballet. Schnittke had particularly close ties with the city of Hamburg. He lived in the Hanseatic city for many years: he taught at the music university, worked with his publisher Sikorski and cultivated a close artistic partnership with John Neumeier, the head choreographer and director of the Hamburg Ballet.

Between east and west

Born in Engels (capital of what was then the Volga German Republic) in 1934, Schnittke moved to Vienna in 1946 when his father, a journalist, was transferred there. Another move followed just a few years later, to Moscow, where Schnittke studied choral conducting and composition. He initially made a name for himself with soundtracks for Russian films, but soon also established a reputation as a concert music composer – with great orchestral works as well as captivating chamber music. In his work he referred to very different styles of music and developed mixed genres, thereby establishing what came to be known as polystilism.

His music quickly made an impact in the west and was championed by prominent figures such as the legendary Gidon Kremer. In the Soviet Union, Schnittke’s musical language was regarded as too experimental and unsuitable for representing the government’s cultural policy. In 1990, Schnittke and his family moved to Hamburg, where he remained until his death in 1998.

The Hamburg musicologist and journalist Lutz Lesle (*1934) met Alfred Schnittke personally a number of times. In a detailed portrait for Elbphilharmonie Magazine (Issue 1/21), Lesle writes about the exceptional composer, exploring the music and the man behind it.

The master of circular time :Lutz Lesle on the composer Alfred Schnittke

Starting from the Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk, a wave of strikes spread across Poland in 1980, resulting in the official approval of the Solidarność trade union in early September. A few days later, a violin concerto by a composer from the Soviet Union whose name was vaguely familiar to me was performed at the Warsaw Autumn Festival – which was at that time the only platform for contemporary music behind the Iron Curtain, and one that was eyed with suspicion by Moscow. I had only come to hear of the composer because the Hamburg music publisher Sikorski, who represented Russian composers (who had to fight for recognition in their own country) in the »free world«, had already identified him as a promising talent.

Soviet ensembles had to undergo certain authorisation procedures to travel even to other socialist countries, so the Poles considered themselves lucky that the Orchestra of the Moscow Conservatory actually arrived and brought with them a work that had been premiered there the previous year: Alfred Schnittke’s Concerto No. 3 for Violin and Chamber Orchestra. With Oleg Kagan, to whom the work was dedicated, as the soloist, the Russians gave the piece an enthusiastically received Polish premiere.

Oleg Kagan plays Schnittke’s concerto for violin and chamber orchestra No 3 (Moscow, 1989)

The contrast between the tonal and atonal

A lot of thought had, of course, gone into the concert programme: Schnittke’s new violin concerto was preceded by Paul Hindemith’s Kammermusic No. 2, and followed by Alban Berg’s Kammerkonzert. These two composers had been Schnittke’s inspiration as he developed his own sound concept.

The order of the programme thereby identified him as the heir of Germano-Austrian music culture: after all, Hindemith’s Kammermusik (1924) comes just as close to Johann Sebastian Bach’s polyphonic art of composition as Berg’s Kammerkonzert (1923–1925) comes to the aesthetic self-conception of the Second Viennese School led by Arnold Schönberg. Schnittke himself said that, for him, it was mainly about »the contrast between the tonal and atonal«. However, he also drew on other sources of inspiration, including old Slavic sacred music and German Romanticism.

In this wealth of connections, one of the constant features of his music reveals itself: its »inner objective« or spiritual message. Arising from the heterogeneous cultural fabric of his family background, the music carries more or less recognisable symbols, allusions, tone qualities, codes and chiffres – strands of resounding meaning and signifying that convey Schnittke’s concept of a synergy of different times and places in one and the same work. He combines various kinds of sacred singing as well as tones from a variety of epochs, stylistic levels and social spheres.

Time planes merge

To capture this multiplicity, Schnittke developed his polystylistic approach: a combination of various stylistic levels, a parodistic jumping between near and far, high and low, density and emaciation. All this is based on the notion of circular time that merges the past, present and future.

As, for example, in the Concerto Grosso No. 3 from the fivefold anniversary year of 1985, which paid homage to Heinrich Schütz, Johann Sebastian Bach, Georg Friedrich Handel, Domenico Scarlatti and Alban Berg. When I met Schnittke again in October 1986, one year after he’d suffered his first serious stroke on the Caucasian Black Sea coast, in Hamburg’s »Vier Jahreszeiten« hotel (Sikorski certainly knew how to look after their protégé), he explained that the polystylistic structure of his Symphony No. 4 for Soloists and Chamber Orchestra was intended to bring together the three strands of Christianity – Catholic, Orthodox and Protestant – with original Jewish temple singing. Accordingly, he combined elements of old Russian »znamenny« chant, Gregorian chant, Lutheran chorale and synagogue cantillation. His focus was on what the various liturgical traditions have in common, rather than on what divides them.

Alfred Schnittke: Concerto Grosso No 3

»Nowhere do I have a natural right of residence«

Even though he chose to be baptised as a Catholic in Vienna in 1982, faith was more important to him than any denomination. »There is a happy point where they all meet«, he assured me. »When you travel the earth, spatial contradictions become apparent. But when you fly high above it, these disappear. It’s the same with faith.« That’s why he combined various »faith tones« in layers in his Fourth. So you could call it an ecumenical symphony, I concluded unchallenged.

When you consider Schnittke’s attitude to life, Gustav Mahler’s (who also converted to Catholicism) feeling of being lost to the world inevitably comes to mind: »I am thrice homeless«, said Mahler, »as a native of Bohemia in Austria, as an Austrian among Germans and as a Jew throughout the world.« Although connected to three cultural spheres – German, Russian and Jewish – Schnittke also felt homeless deep in his soul: »Unjustified sympathy is my fate – nowhere do I have a natural right of residence.« When in a discussion concert the conductor Gerd Albrecht paid tribute to the »endless adagio« in Schnittke’s Epilogue to John Neumeier’s ballet »Peer Gynt« and addressed the composer with the words »Mr Schnittke, you as a Russian…«, Schnittke interrupted: »I am not a Russian. I am a homeless Jew, a Jewish nobody.«

»Of all composers from past epochs, Mahler is the one I feel the closest kinship with.«

Alfred Schnittke

It is no surprise that Schnittke found Mahler’s sound world compatible with his own. Its allusions, its unexpected breaks, diversions and ambiguities, its breakups of material unity as well as the irritating juxtaposition of the tragic and the trivial are just as prevalent in his own work. »Of all composers from past epochs, Mahler is the one I feel the closest kinship with«, he said.

However, alongside the German inheritance, flanked by Bach and Mahler, Schnittke’s music also exhibits traces of his Russian environment – not least in touches reminiscent of Dmitri Shostakovich, the divided father figure of many insubordinate musicians in the Soviet state, and of his penchant for the motorically distorted grotesque. Schnittke openly expressed his admiration of Bach and Shostakovich by invoking their names with the note monograms B flat-A-C-H(B) and D-Es(E flat)-C-H(B) in a number of his works.

Ballet and film music

Six months after our conversation on the banks of the Inner Alster, Schnittke was staying in Hamburg again to attend rehearsals of the ballet »Peer Gynt«, which featured his own music. One day during those rehearsals, I asked him about his experiences in the early days, when, constricted by aesthetic rules, it was almost a matter of survival.

He was writing a lot of film music back then, he explained, and worked with famous directors such as Alexander Mitta, Larisa Schepitko and Elem Klimov. »Out of necessity, certainly.« But plenty of good came of that too: »I was forced to climb down from the high horse of my early doctrine«. Music, he had once believed, must not engage with content (that extends beyond it), incorporate sounds from different eras or other parts of the world, or sully itself with »lower idioms«. By now, even the line between religious and secular music is fluid for him, he says.

Trailer: John Neumeier’s Ballet »Peer Gynt«

Schnittke was always excited about the idea of cultivating genre combinations in order to generate interactions between different styles and sound milieus in one and the same piece, so it can sometimes be difficult to unanimously assign a work to one genre. Almost all the concerti grossi could also be regarded as instrumental concertos. In the Concerto Grosso No. 1 (1977), the harpsichordist, the pianist and the two violinists play a double role in which they perform as soloists and as »group leaders«. The Concerto Grosso No. 5 (1991) seems like a veritable violin concerto. The Concerto Grosso No. 6 (1993) poses as a piano concerto in the first movement, as a violin concerto in the second, and as a double concerto for violin and piano in the third. And Schnittke also called his Concerto Grosso No. 4 (1988) his Symphony No. 5: »The work begins as a concerto grosso and ends as a symphony.«

The century’s sense of being

I will never forget the great Alfred Schnittke retrospective organised by the Stockholm Concert Hall in October 1989, during which anyone in the Swedish capital who had a taste for music with substantial »underwater parts« (to borrow Schnittke’s words) went wild. No one could have dreamt that the event would be such a success: more than 40 works performed over ten days, and the audience growing with each one. There was widespread speculation about the musical seduction strategies of a composer who (visibly affected by stroke) as a figure of suffering, emotional, almost incredulous, accepted the reverence, indeed the declarations of love, from the Stockholm public.

And even the most conservative member of the audience intuitively sensed: in the becoming and fading away of the musical stream, in the changing of stylistic elevations, in the deceptive, often melancholic echo of familiar notes, as it drew to a close, the century’s sense of being became refracted.

Feverish compulsion to create

In the final eight years of his life, which he spent under the wing of the Sikorski publishing empire in Hamburg, Alfred Schnittke felt an enormous compulsion to create (which left him very little time for his teaching work at the music university). Right in the middle of work on his first opera »Life with an Idiot«, which had interrupted his resumed exploration of the Faust figure, while the Vienna State Opera pressured him regarding a stage project about the Renaissance composer Gesualdo da Venosa, Schnittke suffered a second serious stroke in the summer of 1991. Luckily, he once again survived the ordeal. In the Hanseatic city (which awarded him the Bach Prize in 1992), in a feverish burst of creativity between autumn 1991 and spring 1994, he produced an incredible late oeuvre of more than two dozen compositions, among them three operas and three symphonies (numbers 6 to 8), eight orchestral works (including the Concerto Grosso No. 6), chamber music, choral works and songs.

Unsuccessful operas

He then suffered a third and a fourth stroke. Of his three operas, only the first, »Life with an Idiot«, based on an absurdist story by Viktor Yerofeyev (premiered in Amsterdam in 1992), was a resounding success. The opera project about the jealous murderer and chromatically contrite madrigal composer »Gesualdo« (premiered in Vienna in 1995) was ill-starred from the very beginning. Schnittke was fascinated by the subject – the artist’s entanglement with evil – but there were regular disagreements with the librettist.

The »Historia« of the magician and necromancer Johann Faust who famously sold his soul to the devil (premiered in Hamburg in 1995 with conductor Gerd Albrecht) is more like a patchwork rug, although the libretto remains very close to the original old German text, Johann Spies’s book of folk tales (1587), and offers the music more possibilities for »moral« nuance than the Gesualdo model. Whether that was due to the long artistic incubation period or the composer’s physical decline – the opera only »really gets going« in the third act, in which he included his Faust cantata »Seid nüchtern und wachet…« of 1983.

On 3 August 1998 his weary body gave up. Although he was a German citizen and a Catholic, Schnittke’s body was taken from Hamburg to Moscow, laid out in a Russian Orthodox church and buried in the cemetery for prominent figures at Novodevichy Convent. After his passing, things gradually became quiet around him and his legacy. But it is now time to listen again. And it is time for a re-evaluation of his life’s work.

Text: Lutz Lesle, Date: January 2021

Translation: Seiriol Dafydd