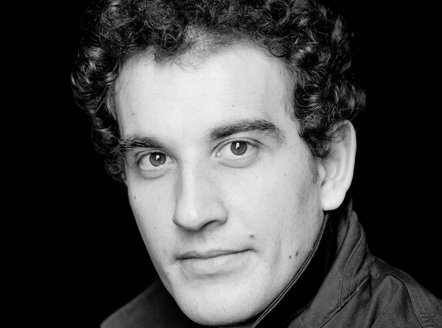

Interview: Bjørn Woll, November 2025

The chemistry has to be right, says Manfred Honeck as he explains his exceptionally long tenure as the music director of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. He has extended his contract with this distinguished orchestra several times, thanks in large part to its willingness to »do its utmost in the collaboration«. His current contract runs until 2028, by which time he will have spent twenty years shaping the Pittsburgh Symphony’s sound and leading it to the Salzburg Festival, where American orchestras remain a rarity.

This highly successful conducting career did in fact begin with string instruments. Born in Vorarlberg in 1958, Manfred Honeck first studied violin and viola at the University of Music in Vienna and went on to become a violist with the Vienna Philharmonic in 1983. Then, in 1987, he changed direction, becoming assistant to Claudio Abbado with the Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra (with whom he appeared at the Elbphilharmonie last August). This was followed by positions as principal conductor at the Zurich Opera House (1991–1996), chief conductor of the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra (2000–2006), and general music director of the Stuttgart State Opera (2007–2011). In 2008, he crossed the Atlantic to Pittsburgh, where he found a musical home – all while continuing to appear internationally as a sought-after guest conductor with the world’s finest orchestras.

For the opening of the Hamburg International Music Festival 2026, Honeck is bringing a rarely performed, large-scale work to the Elbphilharmonie for the first time: Franz Schmidt’s oratorio »Das Buch mit sieben Siegeln« (»The Book with Seven Seals«, 1937), with a score that narrates the Book of Revelation of St. John with six soloists, a large choir and orchestra. Prior to that performance, he is due to provide the musical backdrop for the New Year at the Elbphilharmonie with a programme celebrating the 200th birthday of Johann Strauss (son).

Mr. Honeck, as an Austrian who studied in Vienna, do you feel a special affinity with the music of Johann Strauss (son)?

Manfred Honeck: Yes I do, I simply can’t deny it. For me, it also has something to do with language, because the way you speak shapes the way you think and that in turn influences how you play. So the language alone already sets the scene with an idea of the individual sound. In Vienna, I learned early on not just to play a polka at top speed but to understand its content and character first. And that’s something I want to pass on.

With Franz Schmidt’s »The Book with Seven Seals« you will soon be bringing another work by a Viennese composer to the Elbphilharmonie. Looking at the two of them, the composer Strauss who spawned the Austrian »Schlager« genre and the late Romantic Schmidt, who was two generations younger and often criticized as too conservative for his time: do you see a common thread, something like a typical Viennese sound tradition?

Schmidt’s musical language emerged naturally from the spirit of late Romanticism. He was a cellist with the Vienna Philharmonic and was therefore, as a musician, deeply immersed in the musical language of his time. I don’t see any difference between him and Brahms or Bruckner. He also loved Johann Strauss and played his music. But Schmidt evolved; he didn’t remain in the world of Brahms, Bruckner or Mahler. He developed his own musical voice, at times very bold and reaching far into the 20th century.

What kind of work is »The Book with Seven Seals«, which is so rarely performed?

For me, it is a key work, one of the most important oratorios of the 20th century. The daring sounds and musical subtleties he offers up in the work are immense. This is not run-of-the-mill romanticism at all; instead you have to uncover it. Schmidt’s apocalyptic vision is also frighteningly relevant in our time, although he ends the work with a powerful, hope-filled Hallelujah chorus: the triumph of humanity. It is incredibly profound, serious, but also hopeful music that leaves me speechless. All the highs and lows that a person can experience can be found in this work.

How do you approach such a monumental piece, or any work for that matter?

I want to get to the very core of the works I conduct. By that I mean not only the character of the music, but also the traditions that accompany it. For example, I always listen to older recordings because I want to know how this music was understood in the past. And I really study the circumstances surrounding how they came into being. I want to interpret music in such a way that it can be heard anew. That isn’t my primary intention though. It is simply the result of studying the works closely, because it brings in new ideas that allow some things to appear in a new light.

For a long time, the various great orchestras of the world were said to have their own distinctive sound. Do these sound traditions still exist, or are they increasingly disappearing due to globalisation? To put it another way: Can you distinguish an American orchestra from a European orchestra by its sound?

The differences still exist, but they are no longer self-evident – and there are several reasons for this. Pittsburgh plays differently than Cleveland, New York differently than Chicago. And where do these differences come from? They stem from the fact that conductors at that time stayed with an orchestra for a long time: they had a clear idea of the sound they wanted and communicated this to an orchestra over a period of twenty or thirty years. Some say that the Pittsburgh Symphony sounds more European than other American orchestras. That isn’t surprising as my immediate predecessor there was Mariss Jansons and I’ve now been in Pittsburgh for 18 years. So, over the last three decades, two European conductors have shaped the orchestra’s foundational sound. Of course, there are also special cases. The Vienna Philharmonic, for example, does not have a principal conductor. So they make sure that they continue to develop their own sound with guest conductors. But I see a great danger nowadays. On the one hand, when technically outstanding musicians might pass auditions and be accepted into an orchestra without having grown up in a particular sound tradition. So a certain globalisation is also taking place here when an orchestra does not engage diligently with its own sound tradition and ensure that new members fit into this desired sound ideal.

And on the other hand?

The other thing is that conductors today often settle for having good conducting technique and ensuring that everything runs smoothly from a technical point of view. Rehearsal time is often limited and so it has become commonplace to just make sure that everything is in sync. And that is dangerous! Conductors have to work on the sound, but in order to do that you have to know how to develop a specific sound. That skill has been lost a little in recent decades. Technical perfection alone doesn’t move me emotionally. We need to move away from technical perfection and toward musical perfection, otherwise I get bored at a concert. And that would be fatal!

How do you define a sound tradition in specific terms? Let’s take your own orchestra in Pittsburgh, the Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra, which you performed with at the Elbphilharmonie in August, and the NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchestra, which you’ve known well for many years. How do they differ?

The Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra is made up of teenagers and young adults. They are all excellent musicians, but they are not yet so deeply embedded in professional orchestral life. So there is still room to shape a sound, partly because there is a great deal of openness. In Pittsburgh, the orchestra already played fantastically under Lorin Maazel, whose hallmark was great precision. Then later, Mariss Jansons demanded the same thing, but he also brought his own expressiveness and humanity to the table. Taking on this foundation, I then cultivated a tradition that I had become familiar with in my youth in Vienna: putting technique and expressiveness at the service of music, at the service of performance practice. That’s why I regularly conduct Johann Strauss with the Pittsburgh Symphony. Everyone who plays and conducts him knows how difficult it is. His music sounds incredibly light and buoyant, but the secrets of rubato playing, the subtleties of the soft, quiet sul tasto in the strings, the small nuances that transform a Strauss waltz into a melody – these are a school of their own. And that, to me, is something distinctly European. So I am really looking forward to the New Year’s Eve concert in Hamburg, full of music by Strauss, because the NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchestra also masters that individual rubato playing and puts the expressive content of the music very much at the forefront.

Whether it’s Johann Strauss, Franz Schmidt, or any music in general: what do you hope the audience feels when leaving one of your concerts?

My greatest wish is for people to leave saying: I’ve never heard it like that before. Something has to happen on stage, something audiences can reflect on afterwards on their way home. Or something that excites them. That’s perfectly fine too, because then I know the message has gotten through. The worst outcome for me would be if they left with a feeling of indifference because the music hadn’t touched them in any way.

This interview appeared in German in Elbphilharmonie Magazine (Issue 1/26).

- Elbphilharmonie Großer Saal

Franz Schmidt: Das Buch mit sieben Siegeln / Manfred Honeck

NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchestra / MDR Radio Choir / NDR Vokalensemble / Maximilian Schmitt / Tareq Nazmi / Christina Landshamer – Hamburg International Music Festival Opening Concert

- Elbphilharmonie Großer Saal

Franz Schmidt: Das Buch mit sieben Siegeln / Manfred Honeck

NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchestra / MDR Radio Choir / NDR Vokalensemble / Maximilian Schmitt / Tareq Nazmi / Christina Landshamer – Hamburg International Music Festival