Text: Ivana Rajič, 22.05.2024

Translation: Clive Williams

He is one of the most influential and controversial figures in music history: the composer, theorist and painter Arnold Schoenberg, who would have celebrated his 150th birthday in 2024. Loved and almost revered as a prophet of biblical proportions by some, rejected or even ridiculed by others. Hardly any other term is associated with his name more than that of twelve-tone music. Perhaps irritating terms too, such as the emancipation of dissonance or atonality, which stubbornly remain synonyms for brittle, hard-to-understand, and lacking in entertainment value – music that is cerebral rather than emotional. In other words: born from maths instead of the imagination. As a pioneer of modernism, Schoenberg long remained a kind of musical Einstein – famous, but misunderstood. (He was also friends with Einstein.) However, the composer, who was perceived as cool and strict, suffered greatly from the fact that he was seen as a »dissonant experimenter«: »I would like nothing more than for people to think of me as a better kind of Tchaikovsky.«

ON THE NECESSITY OF »UGLY« MUSIC

In his »Harmonielehre« (Theory of Harmony), published in 1911, the Viennese-born composer wrote: »The artist does nothing that others consider beautiful, but only what is necessary for him.« So someone had to compose »ugly« music. Because: »New music is never beautiful from the outset,« he emphasised 20 years later in a radio lecture on contemporary music, adding: »You know that not only the works of Mozart, Beethoven and Wagner initially met with resistance, but also that Verdi’s ›Rigoletto‹, Puccini’s ›Butterfly‹ and even Rossini’s ›Barber of Seville‹ were booed, while ›Carmen‹ was an utter failure at its initial run.«

Schoenberg’s one-movement Chamber Symphony No. 1, which the enthusiastic composer himself later described as a »real turning point« in his artistic development, can easily be mentioned in the same breath as those classics that originally flopped. Its premiere on 31 March 1931, with Schoenberg conducting, went down in music history as the »Viennese scandal concert«. One reviewer reported: »Many people hissed and whistled, while many applauded. Only one thing should be noted. Mr Schoenberg is happening in Vienna. He makes wild, unkempt, democratic noises that no genteel person could mistake for music.«

In Focus: Arnold Schoenberg

To mark the 150th anniversary of his birth, the Elbphilharmonie is dedicating a spotlight to Arnold Schoenberg in the 2024/25 season, highlighting all of his creative periods.

The piece opens the door to the future right at the beginning, after a kind of motto with a powerful theme rising in fourths on the horn: harmonically, it leaves everything open at first, but is integrated into tonality after a few detours.

The abundance of material, the highly expressive tonal language and the complex harmony, which heralds the dissolution of tonality – parallel to the dissolution of the figurative element in painting –, were largely met with incomprehension at the time. For our modern ears, on the other hand, the Chamber Symphony is clearly part of the Late Romantic tradition and goes down like butter. This is because music history has progressed and the fundamental battles of the past have long since been settled. Today, we can look at Schoenberg and his work more impartially than ever before, leaving the platitudes and misgivings of the past behind us. »The music will frighten you at first. But believe me, if you know it as well as I do now, it will get into your ears like a Mozart symphony,« said conductor Georg Solti in 1966, and 60 years later he may well be right in his assumption.

A VERY LATE ROMANTIC

At least at the beginning of his career, Schoenberg was indeed a Late Romantic as well. His early works were influenced by the music of Johannes Brahms and Richard Wagner. »Harmonies characterised by subdued runs express the beauty of moonlight« – this was Schoenberg’s atmospheric description of the fourth of five sections from his »Transfigured Night«, composed in 1899, in his »Style and Thought«, in which he looked at Richard Dehmel’s poem of the same name, the best-known theme of the Romantics.

-

Richard Dehmel’s »Verklärte Nacht«

Zwei Menschen gehn durch kahlen, kalten Hain;

der Mond läuft mit, sie schaun hinein.

Der Mond läuft über hohe Eichen,

kein Wölkchen trübt das Himmelslicht,

in das die schwarzen Zacken reichen.

Die Stimme eines Weibes spricht:

Ich trag ein Kind, und nit von dir,

ich geh in Sünde neben dir.

Ich hab mich schwer an mir vergangen;

ich glaubte nicht mehr an ein Glück

und hatte doch ein schwer Verlangen

nach Lebensfrucht, nach Mutterglück

und Pflicht - da hab ich mich erfrecht,

da ließ ich schaudernd mein Geschlecht

von einem fremden Mann umfangen

und hab mich noch dafür gesegnet.

Nun hat das Leben sich gerächt,

nun bin ich dir, o dir begegnet.

Sie geht mit ungelenkem Schritt,

sie schaut empor, der Mond läuft mit;

ihr dunkler Blick ertrinkt in Licht.

Die Stimme eines Mannes spricht:

Das Kind, das du empfangen hast,

sei deiner Seele keine Last,

o sieh, wie klar das Weltall schimmert!

Es ist ein Glanz um Alles her,

du treibst mit mir auf kaltem Meer,

doch eine eigne Wärme flimmert

von dir in mich, von mir in dich;

die wird das fremde Kind verklären,

du wirst es mir, von mir gebären,

du hast den Glanz in mich gebracht,

du hast mich selbst zum Kind gemacht.

Er fasst sie um die starken Hüften,

ihr Atem mischt sich in den Lüften,

zwei Menschen gehn durch hohe, helle Nacht.

The poem is about a night-time walk taken by a couple, during which the woman confesses to her lover that she is pregnant by another man. We experience the later Jens Quer – a pseudonym of Schoenberg’s, short for »weird, awkward fellow« – here as a young man: he is just 24 years old and still very much a child of his time. Probably the first programme music for chamber ensemble, his »Verklärte Nacht« retells Dehmel’s verses in music without any text. In the second of five parts, for example, after a dramatic build-up of tension in the dotted viola motif, one hears the words »Ich trag ein Kind, und nit von dir« (I’m carrying a child, and it’s not yours).

And in the fourth section, we hear in calm music the man’s response as he accepts the »other man’s child« as his own.

PIERRE BOULEZ CONDUCTS SCHOENBERG’S »TRANSFIGURED NIGHT«

It would be years before Schoenberg turned his back on tonality, and more than two decades before he published his revolutionary method. But even then, he was unable to abandon his Late Romantic beginnings. In 1916 he wrote a different version of »Verklärte Nacht« for string orchestra, which he revised again in 1943. His twelve-tone technique was not a »zero hour«, but it was absolutely logical for Schoenberg himself: he was merely continuing certain tendencies in the harmony of Wagner, Liszt and others. Thus he saw himself as evolutionary, not revolutionary, and took his place in the ranks of his great predecessors.

»I don’t attach so much importance to being a musical enfant terrible, I just aim to be a natural continuer of good old tradition, correctly understood!«

Arnold Schoenberg

He finally brought the Late Romantic style to perfection with 1913’s monumental »Gurre-Lieder« for an enormous orchestra, six soloists, three male choirs and a mixed choir – particularly impressive in the hymn-like choral finale, which transforms the tragic love story of Waldemar and the deceased Tove into a cosmic union. Here, too, the tonality is widely stretched, but it is still utilised to create forms with a symbolic character: Schoenberg saves C major until the end, making the redemption sound all the more radiant. The triumphant success of the »Gurre-Lieder« premiere in the same year as the »scandal concert« probably confirms his judgement that fundamentally new music must initially meet with rejection – but also shows what a brilliant composer he was.

Free and playful

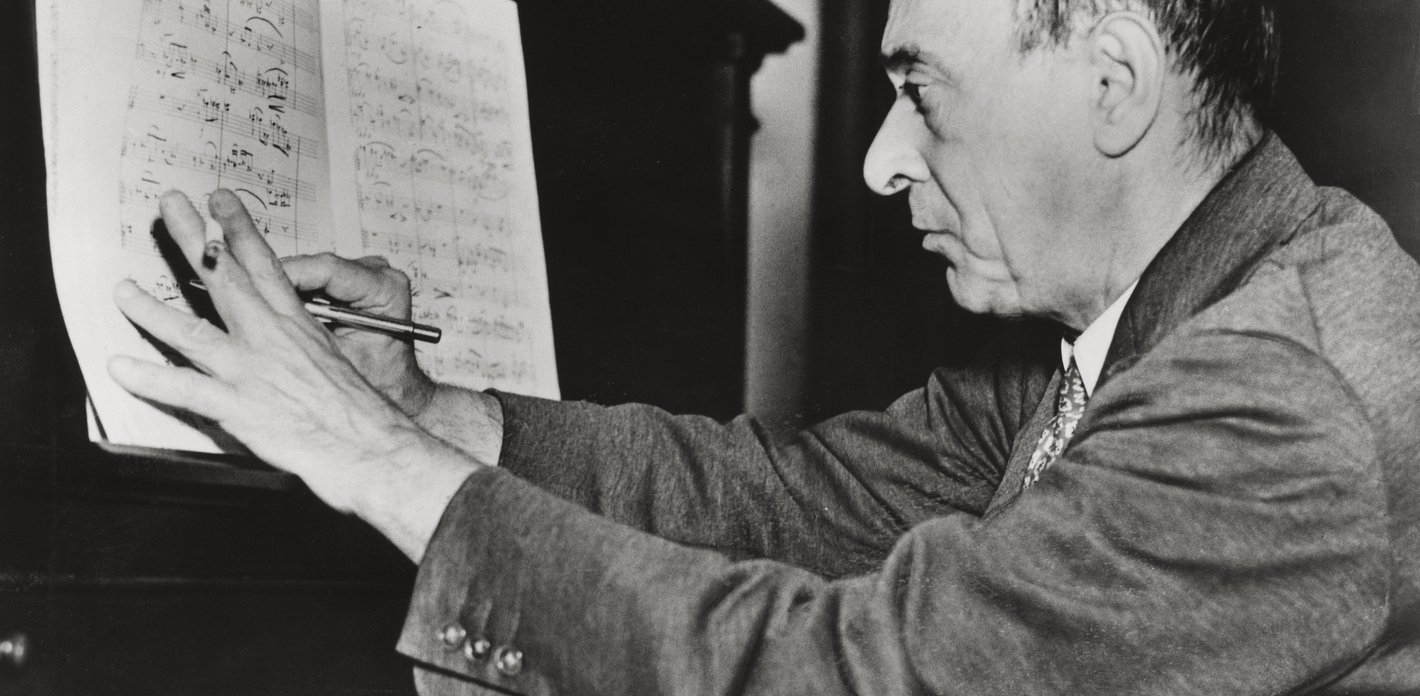

Schoenberg composed his first twelve-tone works in 1923 – using a method based on the simple idea that all the notes in the chromatic scale are equal. They are arranged in a specific sequence and this sequence becomes the basis of the entire composition. Anyone who regards the twelve-tone technique as a restriction on creativity is mistaken. The possibilities for the actual sequence of notes and combinations of sounds from the row are very diverse – as shown by the turntable (pictured) that Schoenberg created for his Wind Quintet op. 26 in order to playfully vary the row and explore its possible combinations.

Schoenberg’s starting point was the musical idea, not the system, so the oft-levelled criticism that his writing is mechanical is misplaced. »I am in a position to compose as unhesitatingly and fantastically as only a young man does, and yet my work is clearly subject to aesthetic control,« he wrote to the Viennese composer Josef Matthias Hauer at the time. »Because I can provide rules for almost everything«. For example, the division of the row in the fourth movement of his Suite for Piano op. 25 into three four-note sequences: E-F-G-D flat / G flat-Es-A flat-D / B-C-A-B flat (the »crab«, in which the row is read from back to front, contains the famous B-A-C-H motif, the letter H denoting the note B in German notation). He uses one as an ostinato, i.e. a constantly repeated figure, and the other two as melodic motifs.

The titles of the suite’s movements – Prelude, Gavotte-Musette, Intermezzo, Minuet-Trio and Gigue – refer to Baroque music and make it clear that Schoenberg can still draw on traditional forms with his new method, and will continue to do so in the future. His only piano concerto (1942), for example, refers to the solo concerto tradition of the past. The unaccompanied piano solo at the beginning is already reminiscent of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 4, but Schoenberg also explores new applications of the twelve-tone method by integrating major and minor sounds into the row structure.

Emotional

Unusually for him, Schoenberg makes clear reference to his own life in the piano concerto. The first sketch sheets contain an autobiographical programme that describes the characters of the four parts in motto style: »Life was so easy« alludes to Schoenberg’s life in Europe before National Socialism, and brings his native Vienna to life with a waltz-like main theme in the piano part. »Suddenly hatred broke out« and »A grave situation was created« allude to Hitler’s rise to power and the persecution of the Jews – expressed by Schoenberg’s »hatred« motif, which in the third movement follows the rhythm of Beethoven’s famous »fate motif«.

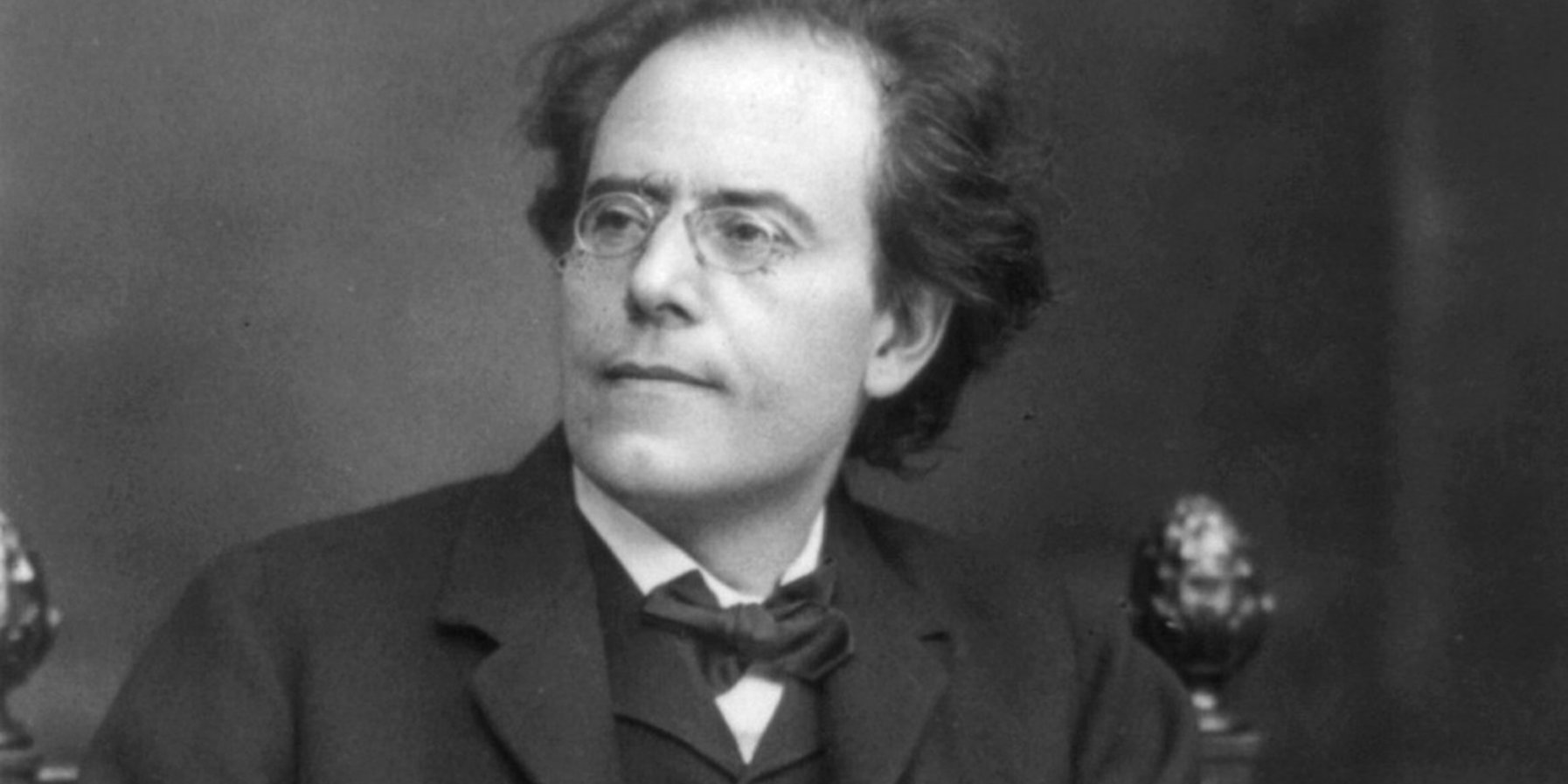

»But life goes on« ultimately refers to the composer’s life in American exile, where it was also to end. »His music has always expressed his emotions,« Schoenberg’s daughter Nuria once emphasised, »and it is neither mathematical nor cold, as some people keep saying«. This undoubtedly applies to the sixth of the Piano Pieces op. 19 as well, with its breathy chords and a mood of resignation evinced in an absence of movement, which Schoenberg wrote in memory of his fellow composer and revered friend Gustav Mahler.

Humorous

We tend to think of Schoenberg as a humourless person, but he actually possessed a talent for light entertainment as well. At the age of 27, he became Kapellmeister at the »Überbrettl«, a Parisian-style cabaret theatre in Berlin. He proved himself to be a master of musical irony and parody with the variety-theatre tone of his »Brettl-Lieder«, setting shallow texts by poets such as Hugo Salus, Gustav Falke or Otto Julius Bierbaum.

Schoenberg is probably best known in cabaret for the character of Pierrot, which became a key work in his oeuvre, and where his humour proves to be particularly complex: Pierrot lunaire op. 21. Pierrot’s attempt in the 18th of 21 poems to wipe a »white patch of moon« off his »black skirt« is as nonsensical as the exaggerated polyphony of the fugue AND the canon that precedes it. And in the first of his Three Satires op. 28 setting his own texts, »Am Scheideweg«, he pokes fun at people »who seek their personal salvation in a happy medium« – including himself, as the word »tonal« is followed by a broken C major triad, which is already contained in the twelve-tone row.

DEMIGOD? NO: A HUNDRED PER CENT HUMAN!

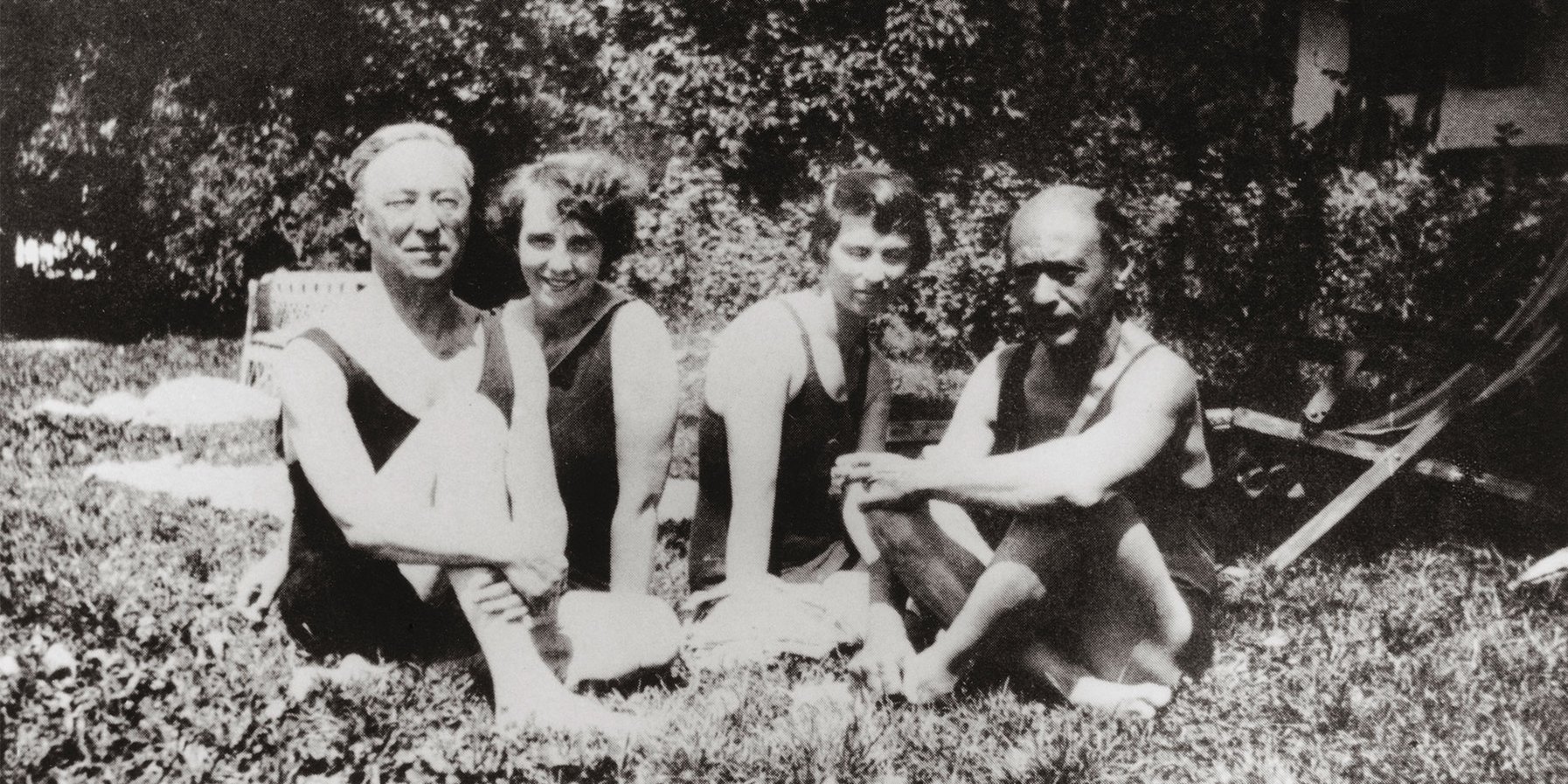

In order to better understand Schoenberg’s ideas and his works, it is worth looking not only at his public persona as a strict musical innovator, but also at the private individual. The composer regularly picked up his painter’s brush, especially between 1908 and 1912, and impressed contemporaries such as Oskar Kokoschka, Franz Marc and Wassily Kandinsky (he was friends with the latter) with his portraits, self-portraits and landscapes. He was also interested in card and board games, even making his own playing cards. He often built his own furniture, invented new transfer tickets for the Berlin tram network, and created a music typewriter and a chess set for four players. He was a keen dog lover, he loved swimming and rowing as well as tennis, which he only learnt to play at the age of 53, and he had a ping-pong room at home where tournaments were held.

A DAY IN THE LIFE OF ARNOLD SCHOENBERG

Schoenberg was also a family man, a »very loving father« of three children, »who had a lot of time for us«, as Nuria Nono-Schoenberg recounts. In a letter to his wife Gertrud, »dearest Trude, dearest, only you and your loved ones around«, he wrote: »I’m fine and I miss your kisses. You must send me lots. I’m sending you – and now comes a one with eleven zeros. 100000000000 kisses« – a twelve-note series that breaks all the rules for feelings. Because, as he asked himself in his »Harmonielehre«: »Why try to be a demigod? Why not be a hundred per cent human instead?«