Text: Peter Reichelt, 14.10.2024

It’s not so long since the EU elections were held, and the outcome was once again frightening: specifically, voters’ strong reaction to the immigration and migration policies. Migration is nothing new, and it has always been important for the cross-fertilisation of cultures and their respective advancement. (As an international port and centre of trade, Hamburg knows all about that.)

Well, things were a little different where Naples was concerned.

Considerably older than Hamburg and blessed with a lot more sunshine, Naples has the best view of Vesuvius as well as long experience with very different migratory movements, both above and below ground. Diffusing, so to speak. Ultimately, it’s no surprise that a city built on such geoactive terrain has also produced such vigorous symbioses of different cultures.

Viva Napoli :21. bis 24. November 2024

Fancy a short trip to Italy? The Elbphilharmonie is celebrating the varied musical culture of Naples over a long weekend –from medieval courtly dances to the trendy singer-songwriter FLO.

A city beneath the city

When it’s part of everyday life that what lies below can come to the surface at any time, people have a different relationship to the life’s essential changeability than in more stable regions. Deep beneath the lively alleyways of Naples lies a »city beneath the city«. A labyrinth of impressive caves, cisterns and fountains some 80 kilometres long runs through the entire underground. The tufa caves lie forty metres beneath the surface and have been used for a wide variety of purposes since the 4th century BC: they have served as secret hideaways, places of worship, catacombs and rubbish dumps. During the Second World War, they offered the population protection from bombing raids, saving many lives.

Originally founded as a Greek colony (Neápolis, the new city), Naples came under the French rule of the Angevins in 1265, and was then part of the Spanish empire from 1442 to 1707. The city oscillated between these two colonial rulers –with Austrian participation – until 1860, when Naples and Sicily joined the new Kingdom of Italy. Today, Naples is the administrative centre of the Campania region. An independent mayor governs a centre-left-oriented city with almost a million inhabitants.

But Naples is also the home of the Camorra, one of Italy’s oldest and largest criminal organisations, whose origins date back to the 16th century.

Folk music and canzoni :Tthe Neapolitan song becomes a recipe for success

It was around this time that the city’s official musical life underwent a revival, after a first heyday in the 14th and 15th centuries and then a shorter period of stagnation: Diego Ortiz, Francisco Martínez de Loscos and Giovanni de Macque provided important impulses for this musical renaissance in Naples as conductors of the court orchestra, which had been in existence since 1444.

If we ask about what were once separate realms – folk music and art music –, we need to differentiate precisely between genuine folk music and Neapolitan song. Traces of the former can be found in the cries of street vendors and in the rituals of some religious festivals such as the Madonna dell’Arco, which conceal an essentially pagan core beneath a Christian façade; the latter, though now widespread across all social classes, originally belonged to a higher cultural sphere.

In Neapolitan song, the folk tradition is mixed with elements of romance, opera buffa and 19th century salon songs. It speaks for itself that the main figure in its golden era around 1900 was a refined poet like Salvatore Di Giacomo; by the same token its musicians, though for the most part talented improvisers, were also skilled composers, such as Paolo Tosti, Luigi Denza and Enrico de Leva.

Luigi Denza: Funiculi, Funicula

The most authentic Neapolitan folk music is found in the countryside outside the city: this has been revived since the 1970s, chiefly through the ethnomusicological research of Roberto De Simone and through modern adaptations like those of the Nuova Compagnia di Canto Popolare. It has also been used in various stage works, the best-known of which is Roberto De Simone’s »La gatta Cenerentola«, 1976). Among other things, this has contributed to the rediscovery of the villanella, a 16th-century verse song, which in turn had its origin in the strambotto, an impromptu form of lute song popular in the 15th century.

Mockery in Neapolitan :Slang on the opera stage

The success of the villanella –perhaps the only musical genre to be invented in Naples before opera buffa – since the 1550s owes much to the use of the Neapolitan dialect (which, incidentally, was officially recognised as a language by the Campania region in 2008) to poke fun at the elaborate madrigal and its conventions. The villanella found its way into many genres and appeared in the most curious places: in the sacred dramas performed in conservatories, in chamber cantatas and in opera. The only surviving comic opera by the composer Leonardo Vinci, »Li zite ’ngalera« (1722), actually opens with a villanella.

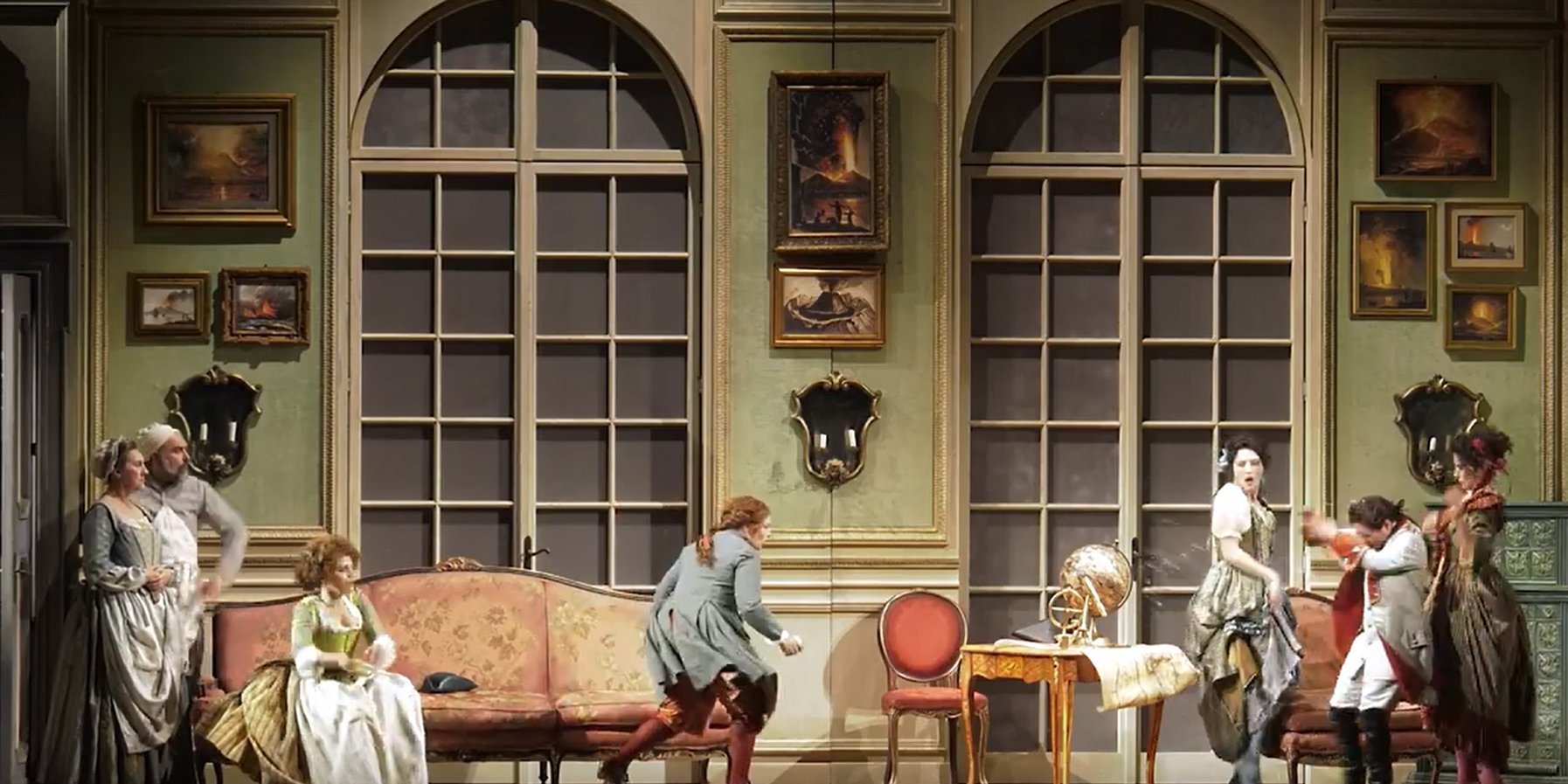

Trailer: »Li zite ’ngalera« (Teatro alla Scala)

Neapolitan was an aspect of the commedia dell’arte tradition that was carried over into opera buffa, comic opera, and established a distinctive Neapolitan style. Contemporary sources provide valuable descriptions of the way operas were performed in Naples at the time, and also provide information about the mutual influences between comedy, sacred oratorio and heroic opera. Giulia de Caro, singer and director of the first Naples opera house, Teatro San Bartolomeo, from 1673 to 1675, had begun her career in the commedia dell’arte - just like her impresaria predecessor, the actress Cecilia Siri Chigi.

Incidentally, for 18th century opera buffa, in which a folk aspect also manifested itself in the use of associated instruments like the shepherd’s pipes zampogna or the South Italian lute colascione, this adherence to the Neapolitan dialect later proved to be a decided disadvantage, as it made the music’s dissemination to northern Italy or even abroad much more difficult.

Traditional major events :Church rites and immortal melodies

Even today, the most revealing examples of the indestructible stylistic ambiguity of Neapolitan music are the impressive religious festivals and processions such as the cult of the Madonna dell’Arco. It is widespread throughout the province and in the city of Naples, and has around 150,000 followers who take part in the pilgrimage to the Santuario della Madonna dell’Arco in Sant’Anastasia every year on Easter Monday. In addition, around 30,000 battenti participate in a cycle of public rites in the months leading up to the actual festival.

The ritual practices include the »questue«, a ritual form of begging, and the »funzione«, in which devotees pay public homage to the Virgin Mary in the street, following strictly codified choreographic sequences. The »funzione« in particular takes place in the presence of a band, the divisione musicale, which accompanies the ritual and the coordinated actions of the battenti. The funzioni are organised and performed by more than 600 cultic associations based in different Neapolitan neighbourhoods and provincial towns, which plan their own rituals almost completely independently of one another. These circumstances, as well as the commitment to a ritual schedule, allow a rough estimate of the number of participants: considering that each »section« consists of between five and twenty people, one could guess that more than 1,000 musicians in the entire province of Naples take part in this major event.

Some of the music they perform forms part of the standard composed repertoire of all processions and other rites indispensable in southern Italy’s bands, for example popular religious hymns such as »Noi vogliam Dio«, »O Maria, quanto sei bella«, »Mira il tuo popolo, bella Signora« or locally-known songs such as those dedicated to the regional patron saints. However, very different pieces are also performed together with the traditional numbers, such as adaptations of film music or pop songs; these in turn reflect the musical socialisation of the predominantly young band members (between 14 and 20 years old!).

Festa dei Gigli in Nola

Another example are the Feste dei Gigli, public festivals that take place every summer in many towns in the province of Naples as well as in surrounding areas. The formal and aesthetic features as well as the practices of the various festivals are very similar, and faithfully follow the Nola model, which is the longest-standing and most widespread.

The Festa dei Gigli in Nola, a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Site, celebrates St Paolino di Nola and his return home after a long imprisonment in the fourth century. Today, however, the devotional nature of the event serves as the backdrop for a spectacular and entertaining spectacle: the festival consists of a 24-hour parade that takes place on the Sunday after the summer solstice, preceded by several events in the months leading up to it. During the parade, imposing structures up to 25 metres high, the »gigli«, are carried through the town streets on the shoulders of a hundred or so bearers, the »paranze«. Where a group of people move such a huge structure with their sheer physical strength, the bearers obviously have to have a high level of coordination and concentration. Ensembles positioned on the »gigli« guarantee safety and effectiveness, rhythmically stabilising the parade’s progress.

Everything goes

The Festa dei Gigli have remarkable special features that clearly distinguish them from similar events, such as the ensembles involved in the parade. Although brass and percussion groups played at the »gigli« until the 1980s, the number of trumpets and saxophones has now shrunk to one or two and other typical band instruments such as clarinets and trombones have been removed, while the electric guitars, electric basses and keyboards common in pop music have been added, and can now be heard over imposing sound systems that are actually set up on the »giglio« and powered by generators. The only element that has been adopted from the »traditional« bands is a drum kit.

The great changes in the musicians’ playing style correspond to the radical innovations in the repertoire performed at the parade. Every year, new, specially written and orchestrated compositions are added. They follow the specific requirements of the various phases of the »giglio« transport, and each has certain rhythmic patterns that facilitate the coordinated movements of the paranze. However, they only form a small part of the overall parade music. Most of the time, long medleys containing song excerpts of different origins are played: TV and cartoon theme tunes, jingles, soundtracks, themes from pop, jazz, disco, funk – nothing is off limits.

A song goes around the world :the story of the hit »O sole mio«

Wussten Sie eigentlich, dass die berühmteste Canzone napoletana, »’O sole mio«, gar nicht in Neapel, sondern in einer politisch heute sehr prekären Gegend entstanden ist?

Der Komponist Eduardo Di Capua befand sich 1898 mit dem Neapolitanischen Staatsorchester auf Tournee. Eines Nachts in der zu dieser Zeit südrussischen – heute ukrainischen – Hafenstadt Odessa konnte Di Capua der Kälte und seines Heimwehs wegen nicht schlafen. Als am Morgen die Sonne aufging und durch das Hotelzimmer schien, kam ihm die Melodie zu »’O sole mio« in den Sinn. Di Capua unterlegte sie mit Versen des neapolitanischen Dichters Giovanni Capurro. »’O sole mio« ist also ungeachtet seines fernen Entstehungsorts ein neapolitanisches Volkslied, das in der Interpretation von so volksnahen Repräsentanten der Hochkultur wie Enrico Caruso, Beniamino Gigli, Fritz Wunderlich oder Luciano Pavarotti um die Welt gehen sollte.

Andrea Bocelli sings »’O sole mio« at the Central Park (2011)

Di Capua also wrote the famous song »O, Marie« and, like Capurro, he died in poverty as there was no copyright law at the time, and thus no royalties for authors. The composer and the poet sold the rights to their worldwide hit to a publishing house for a mere 25 lire. A bitter success story, at least from the authors’ point of view – but one that means there is a little bit of Naples almost everywhere today.

This article appeared in the Elbphilharmonie Magazin (issue 3/2024).

English translation: Clive Williams