Text: Stefan Franzen, August 2025

Catalonia – the name evokes thoughts of Barcelona with its striking modernist architecture, Antoni Gaudí’s Sagrada Família, Joan Miró’s paintings and the music of cellist Pau Casals. It brings to mind the wild Costa Brava, the rugged hills of the Pre-Pyrenees, FC Barcelona’s international triumphs and bizarre customs like the Castells – human pyramids found in the Tarragona region. And inevitably, it also recalls recent political events and renewed calls for independence from Spain.

-

About the historical context

The northeast of the Iberian Peninsula has always stood somewhat apart from the rest. For centuries, it served as a crossroads for peoples moving between the British Isles and the Near East. Moorish influence was felt here too, even though the Caliphate of Córdoba never extended across the entire region. By the late 10th century, after the Arabs withdrew, the emerging counties freed themselves from West Frankish rule. When united with Aragon, the Principality of Catalonia became a major economic power in the Mediterranean. From the 15th century onwards, Catalonia often found itself a pawn caught between larger spheres of influence: co-ruled by Spain, forced to cede land north of the Pyrenees to France, siding with the Habsburgs against the Bourbons and eventually absorbed into Napoleon’s French Empire.

Its brief period of provisional autonomy under the Second Republic in 1931 was cut short only eight years later by Franco’s dictatorship, after a brutal civil war that drove hundreds of thousands of Catalans into exile. The Catalan language – spoken in variants from the French border to the Balearic Islands and Valencia – was banned. Only after the end of fascist rule did Catalonia regain partial autonomy in 1979.

Since then, calls for greater self-determination within Spain have resurfaced time and again. The issue came to a head in 2017, when the region dominated headlines almost daily: 90 percent of voters backed an independence referendum. And when Prime Minister Sánchez pardoned the »sinful« separatists in 2023 to secure a governing majority, Spanish society once again found itself deeply divided – since few are willing to see the economically successful and prosperous Catalonia break away.

Focus Catalunya :12.–16.11.2025

Mediterranean sunshine as an antidote to the grey month of November! For one weekend, the focus is on the diversity of Catalan musical life, from the Middle Ages, symphony orchestras and choirs to folk dances, electronic music and singing star Sílvia Pérez Cruz.

Music like a mosaic

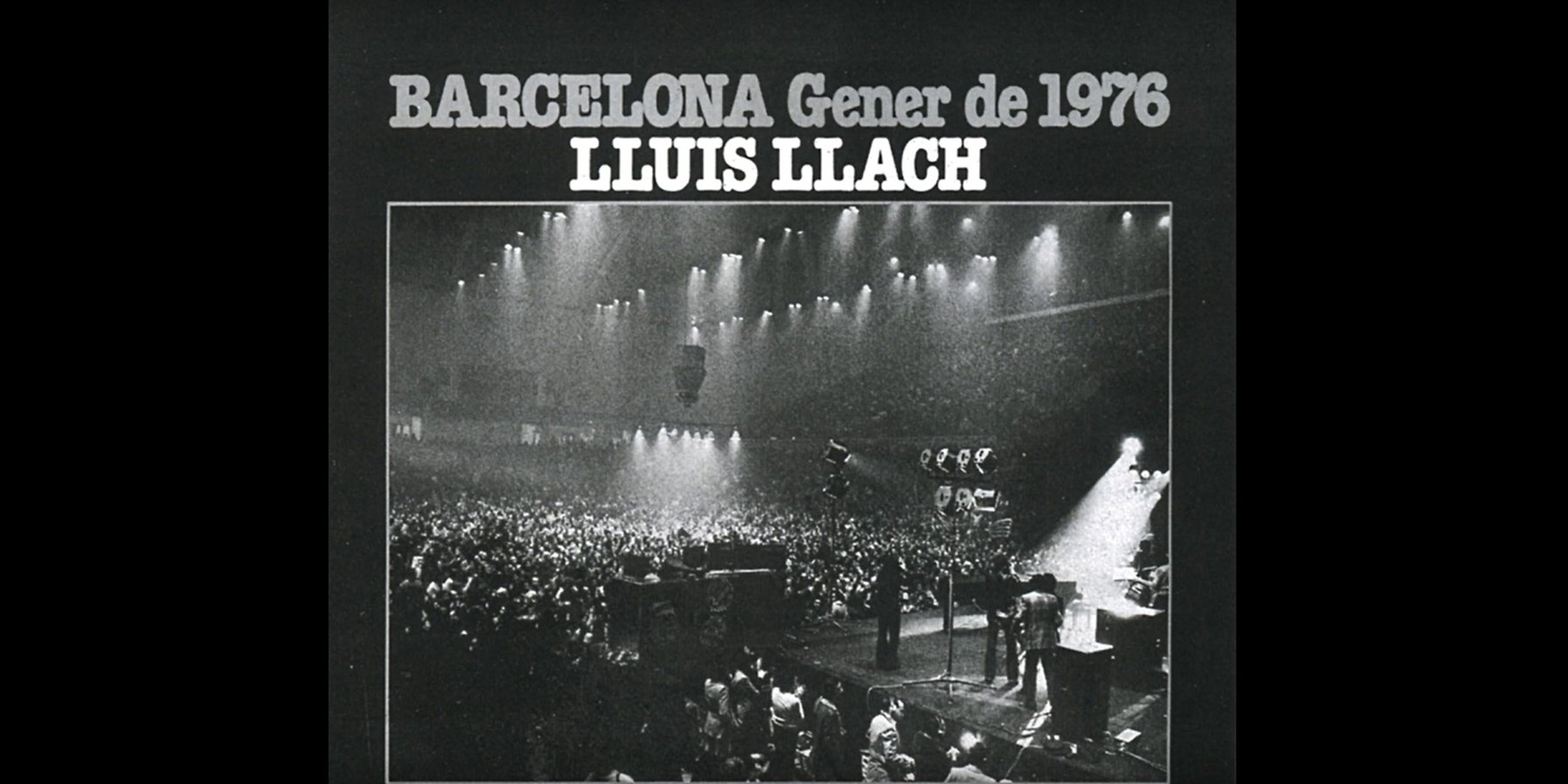

The quest for independence has also left its mark on music. For example, in Catalonia’s secret anthem, »L’Estaca«, written in 1968 by singer-songwriter Lluís Llach: »Can’t you see the stake to which we are all tied? If we all pull, we can bring it down and free ourselves.« This song spread around the world in many languages and became the musical symbol of freedom movements from Poland to Latin America. In 1964, singer-songwriter Chicho Sánchez Ferlosio also revisited the Republicans’ struggle against the coup leaders during the 1930s in his song »Gallo Rojo, Gallo Negro«, a dramatic ballad.

Lluís Llach: L’Estaca

Today, the distinctive musical culture of rebellious Catalonia still carries an air of defiance – but it is now less about separatism and more about connection. It has become a force that unites: a special glue linking the region southward to Valencia, outward to the Balearic Islands and across the Pyrenees to France. Together, these ties shape Catalonia into a cultural nation with a strong international presence and a distinct identity within other regions of Spain. Ensuring that Catalan music forms a dazzling trencadís – a colourful mosaic of porcelain shards – reminiscent of the works of architect Antoni Gaudí.

»Prelude«: the concert introduction (German only) :Focus Catalunya

Dancing in the church

A fascinating early chapter in European music history unfolded in Catalonia. Between bustling Barcelona and the small town of Manresa lies the Benedictine monastery of Montserrat, perched dramatically on a rocky peak and a centre of Marian devotion since the Middle Ages. In those days, pilgrims often spent the night in the church, bringing with them songs in Latin, Catalan and Occitan – which were then woven into the liturgy. And even back then, true to the region’s rebellious spirit, some of these devotional songs were even danced to. Around 1400, this repertoire was compiled into a manuscript that centuries later received a red binding, giving it its present name: the »Llibre Vermell«.

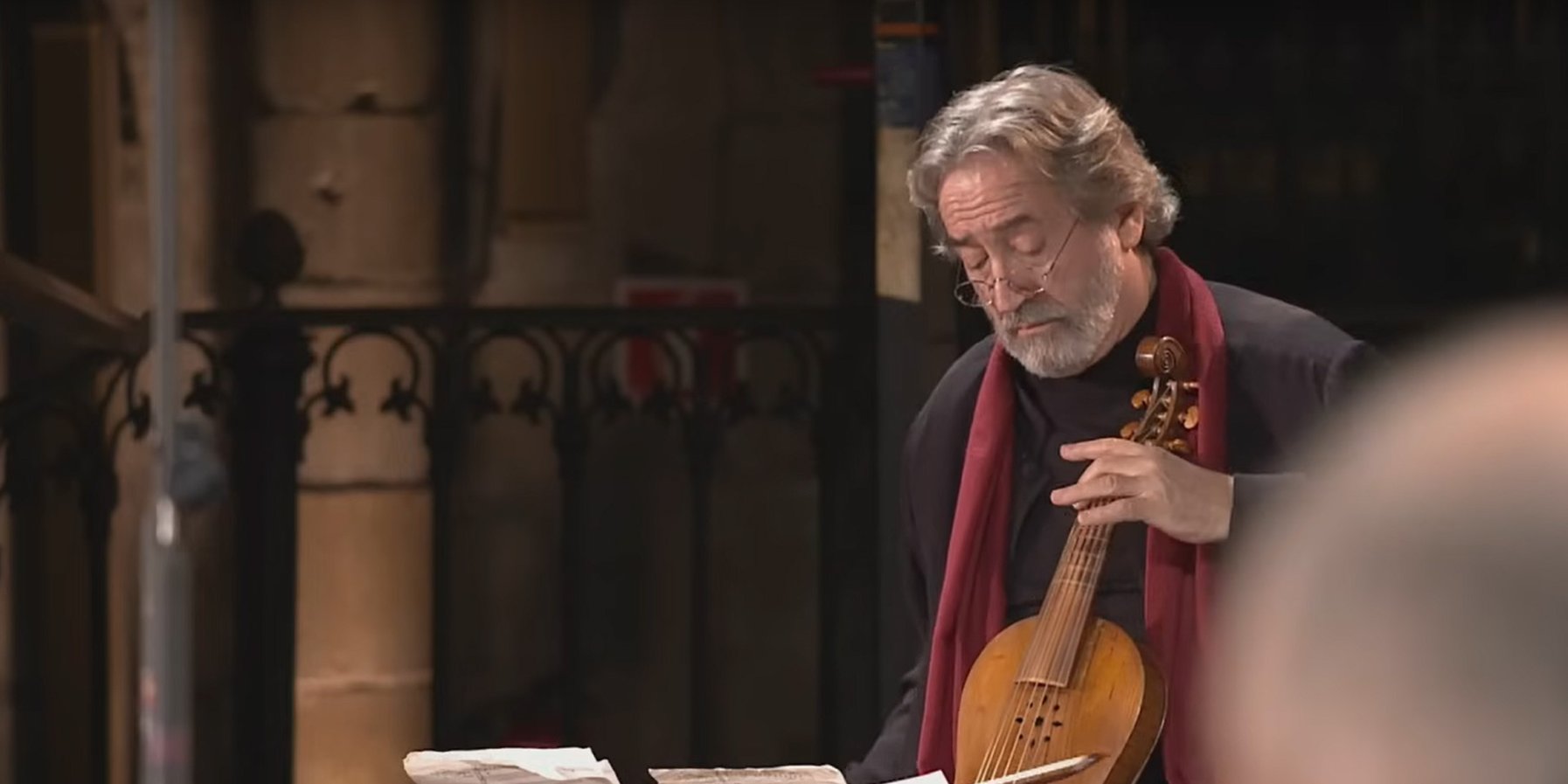

Many performers of our time have taken an interest in this outstanding early testimony to European music. As Catalonia’s leading musicologist, Jordi Savall has also done so with his choral and instrumental ensembles »La Capella Reial de Catalunya« and »Hespèrion XXI«. Since the 1970s, the gambist has devoted himself in particular to early music and its connections to the sounds of other continents. His version of the »Llibre Vermell« set standards 45 years ago.

Jordi Savall: Llibre Vermell

Dancing in a circle

The characteristic sound of Catalonia – the cobla bands with their piercing, powerful shawms – also has roots stretching back to the Middle Ages. The instrument’s predecessors were first played by minstrels in towns and churches before being adopted by rural communities, where their volume and simplicity made them ideal for village festivals. From these early shawms evolved the instruments typical of today: the tenora and its higher-pitched sibling, the tibla, which emerged in the mid-19th century. Returning then to urban settings, they combined with modern brass instruments, inspiring composers to write for these now-institutionalised ensembles, called cobla.

The repertoire consists of sardanas – pieces that exist both as music and as dance. Performed as circular round dances, often outdoors, they became a symbol of Catalan identity, so much so that they were banned under Franco. The artistic concert version is uniquely orchestrated and sometimes funny, sometimes romantic or even melancholic. In addition to the shawms, today’s coblas, usually consisting of eleven members, include the one-handed flute flabiol (the player beats a small drum with the other hand), trumpets, valve trombones and the fiscorn, a kind of mini tuba, as well as a double bass for depth. Sardanas made their way into Catalan rock music in the 1970s, when the Companyia Elèctrica Dharma took to the stage with a cobla band for their hit »Bal Llunatic«.

Classic Catalan

Cobla music is far from outdated. Few European regions see young musicians so passionately engaged with their roots. Studying sardanas and all kinds of traditional music is now considered ultra-modern in Catalonia. Barcelona has its own teaching institution for traditional music, the Centre Artesà Tradicionàrius (CAT). Meanwhile, the Orquestra de Músiques d’Arrel de Catalunya – made up of 20- to 30-year-olds from all Catalan-speaking areas – fuses cobla traditions with jazz, modern classical music and contemporary poetry.

For the past forty years, the Cobla Sant Jordi of Barcelona has stood out as one of the leading sardana ensembles. Over time it has opened its repertoire to jazz, classical music and even flamenco.

Its programme presents sardanas with an astonishing range spanning more than a century, including one written in exile in France by the great cellist Pau Casals.

Of course, sardanas are only a small part of what can be heard in Catalonia’s concert halls. The region’s classical music scene boasts the Orquestra Simfònica de Barcelona (OSB), a symphony orchestra of international renown that also regularly performs local traditions and greats, such as the works of Miquel Oliu (born 1973), who integrates influences from Robert Schumann to Sofia Gubaidulina into his modern musical language. Another towering figure is Federico Mompou (1893–1987), one of the great names in Catalan music history and at the same time probably the greatest maverick among the composers of the Iberian northeast.

Mompou’s starting point in his youth was the then cutting-edge music of Claude Debussy and Erik Satie. He became known above all for his piano cycles, which he wrote over a period of fifty years, culminating in the »Música callada«, the music of silence: sounds of almost ascetic austerity with metallic, bell-like chords, inspired by the writings of the 16th-century mystic Juan de la Cruz. He also wrote songs, later orchestrated, in which melancholic lyricism prevails – simple, folk-like melodies repeatedly interspersed with sophisticated chromaticism.

Youthful voices :The Orfeó Català

Anyone who has ever sat in the Palau de la Música Catalana, that modernist jewel in the heart of Barcelona, will never forget it. Built between 1905 and 1908 by Lluís Domènech i Montaner, the hall is perhaps the most breathtakingly artistic of all concert venues, with its opulently decorated, luminous windows and domes, mosaic columns and sculptures.

The Palau is home to the Orfeó Català folk choir. Its professional ensemble, the Cor de Cambra, has for 35 years been devoted to reviving and safeguarding the musical heritage of Spain’s north-eastern region while also inspiring new creations. Their repertoire spans Renaissance sacred music to contemporary works that reimagine traditional forms such as the sardana, jota and fandango.

This youthful energy in Catalan vocal traditions continues through a number of internationally active ensembles that combine folk with electronic sounds, drawing on a rich wealth of genres. The glosa – a witty, improvised poem often used today to comment on political and social issues – remains popular, alongside the Balearic tonadas and the cants de batre, once sung as work songs. The female duo Tarta Relena relies on the distinctive sound of the Catalan language to modernise old forms. In addition to Catalan and Balearic sources, they also draw on traditions from Corsica, Crete and Georgia, paying homage to Hildegard von Bingen and 21st-century songwriters such as Björk – and in doing so create a contemporary, youthful electronic folk sound, always led by the expressive power of the voice.

Iberian timbre :Sílvia Pérez Cruz

Perhaps no voice defines Catalan music today more than that of the singer and songwriter Sílvia Pérez Cruz. Born in the coastal town of Palafrugell on the Costa Brava, she weaves the character of her home region together with musical traditions from across Spain and Latin America to create a truly global vocal art. She grew up with the habanera – a genre reimported from Cuba and deeply rooted in Palafrugell – where her late father was its foremost researcher. The vehicle for all her musical visions is always the song form, the canción, the chanson. »When I hear a song, I immediately grasp its beauty. It’s the feelings that matter to me; I don’t think in terms of genres like classical or rock.«

This freedom from stylistic and geographical boundaries allows the 42-year-old to uncover the timeless essence of song – whether drawn from Catalan tradition, flamenco, Brazilian music, Portuguese fado or Cuban habanera. Her repertoire ranges from Édith Piaf’s »Hymne à l’amour« and Leonard Cohen’s »Take This Waltz« to the Mexican ranchera »Cucurrucucú paloma«. She has even adapted Robert Schumann’s art songs and daringly paired a motet by Anton Bruckner with the jazz standard »My Funny Valentine«.

»There is so much in a voice that transcends styles or territories, that goes beyond the body,« she explains. »But I can clearly define my timbre as Iberian. It’s something shared by all grandmothers on the peninsula. Something that runs through fado, flamenco, every region. And I carry that in my voice too.« Her singing, despite its naturally high register, can be powerful and earthy one moment, the almost whispering the next, enriched with ornate embellishments and delicate vibrato. It is this mastery of vocal facets that makes a Sílvia Pérez Cruz performance a profoundly moving and unforgettable experience.

Duo project with Salvador Sobral

For her latest project, Sílvia Pérez Cruz has joined forces with Portuguese singer Salvador Sobral, winner of the 2017 Eurovision Song Contest. Sobral, who studied jazz in Barcelona, maintains close ties to Catalonia, making the collaboration a natural fit. The duo performs songs written especially for them by Pérez Cruz’s band violinist Carlos Montfort, alongside contributions from South American luminaries such as Uruguayan Jorge Drexler and Brazilian Dora Morelenbaum. The pianist Marco Mezquida also penned a work for the project. They are accompanied by a stellar ensemble: the cellist Marta Roma, one of the many young virtuosos continuing Pau Casals’s legacy in a 21st-century spirit, and the guitarist Darío Barroso, whose playing moves seamlessly between folk-inspired patterns and flamenco techniques.

Their own style of playing

When people hear the word flamenco, most immediately think of Andalusia. Yet Catalonia has developed its own distinctive Gitano style that has become world-famous: Rumba Catalana, which produced global hits in the 1980s and 1990s with the Gipsy Kings. Later, with the wave of mestizo music sparked by Manu Chao, it re-emerged in a rawer, hip-hop-inflected form through bands like Ojos de Brujo, cementing its place in world music.

Today, Catalan flamenco thrives in exciting jazz projects, such as those led by the guitarist Chicuelo, a disciple of the legendary Manolo Sanlúcar (1943–2022). In his project »Del Alma«, he collaborates with the Menorcan pianist Marco Mezquida, who describes carrying in his DNA both the fishermen’s songs of his island and the melodies of the Pyrenees. »I love the piano itself and all its versatility,« Mezquida explains. »Some of my experiments sound closer to contemporary classical music than to jazz. I’m inspired as much by gamelan as by the church organ.«

Together, Chicuelo and Mezquida take up flamenco rhythms such as zapateado, bulería and tanguillo with great virtuosity, forming their own witty dialogue in an elegantly dancing flow and melodic exuberance, spiced with blues and música latina. And in doing so, they demonstrate once again what so often defines Catalonia: a remarkable blend of cosmopolitan openness and stubborn obstinacy.

This interview appeared (in German) in Elbphilharmonie Magazin (Issue 3/25)