Text: Leonie Reineke, 17 April 2025

It invents stories at lightning speed, generates images with seemingly unlimited imagination and imitates voices with frightening perfection: artificial intelligence has long since assumed a prominent position in the modern digital age. Although it is difficult to grasp as a phenomenon, it has become an integral part of our lives, though even yesterday it still felt like a dream of the future. Nevertheless, AI chatbots often surrender when it comes to questions of logic, producing one error after another. Their sense of humour also leaves a lot to be desired. And precise, differentiated answers to questions within a very specific subject area are not necessarily to be expected. Not yet.

All the more reason for a certain thought to come to mind: If logic and factual information are not at the forefront of AI use, what about an area where the question of right or wrong is rarely asked – the field of art and creativity? Can AI possibly compose music? And if so, can it do it better than we humans?

AI version of Beethoven’s 10th Symphony

If this is making you think, you should know that the question has already been answered – e.g. by a Chinese smartphone manufacturer: in 2019, Franz Schubert’s B minor Symphony, the »Unfinished«, was performed in a »completed« version, with two new movements added that were composed by an artificial intelligence. The AI model developed for this purpose used Schubert’s music to learn the composer’s style, as it were, and went on to compose in that style. What some hailed at the time as a marvel of state-of-the-art technology was viewed sceptically by others – especially in view of the rather banal result: sterile, pseudo-Schubertian music that doesn’t do justice to the original.

A similarly sobering project was the composition of Ludwig van Beethoven’s never-realised »10th Symphony« using artificial intelligence. To write what the Beethoven Orchestra of Bonn premiered in October 2021, a computer spent two years working on the composer’s scores and sketches. But here, too, the result sounds unimaginative and not really like Beethoven – especially as the AI’s supposed performance is open to criticism: an arranger kept intervening during the finalisation of the score, picking out individual passages from the computer results and even doing the orchestration by hand. So a human being was needed after all.

AI Weekend 2025

No technology is currently generating as much discussion as artificial intelligence – in music as well. Concerts with EEG bonnets and 3D sound will be accompanied by a weekend of talks with the artists.

SLICK AND BANAL

You may be disappointed, but perhaps reassured as well. Because one thing is clear: despite all the potential that artificial intelligence offers, a lot of human design is still necessary, especially in the arts. AI – even AI produced by companies worth billions – is only ever as intelligent or creative as its user or inventor. It doesn’t have different, and certainly not better, taste in music. Some models produce meaningless, interchangeable Hollywood soundtracks; others may offer a wider range of musical genres, but even there the limits are quickly reached, and boredom is inevitable.

»I don’t find it really interesting for the artistic process to use the big AI programs like Suno or Udio,« says composer Brigitta Muntendorf, who is making increasingly use of artificial intelligence in her work. »A lot of things are prefabricated, so you hardly have any creative freedom. It’s more exciting working with software where you can intervene in the algorithms yourself. But the standard tools don’t allow that.«

Alexander Schubert, who has been using AI in his compositions for a long time, takes a similar view: »It’s obvious that the big companies’ AI models are trained on mainstream data sets. This means that their output – no matter who the user is – generally also reflects a mainstream aesthetic. Whether it’s images, sounds or stories: you often come across something very slick and crisp, a glamorous, digital hyper-reality – which ultimately just reinforces the mainstream. And that soon lacks interest, of course."

The phenomenon Alexander Schubert is describing can actually be found in many AI-generated images or songs: kitsch unleashed, slickness suitable for advertising and a blandness that gives you the creeps. »And it’s precisely this aesthetic that you get tired of at some point,« says the 46-year-old. "That’s why I’m interested in what new needs this creates in people. There may be a renewed longing for something rough and broken, something that’s not just chic.«

UNEXPECTEDLY JUMPING BACK AND FORTH

Breaking with convention, inventing alternative models of reality and giving space to things that aren’t intact – these have always been among the aims of New Music. It is hardly surprising that the tech-giant AI assistants are not designed for such needs. So in turn it’s no surprise that composers of contemporary music – if they are actually interested in working with AI – prefer to operate with smaller models, where they have access to all of the machine’s learning steps before the final result.

For example, the composer Genoël von Lilienstern joined forces with a few colleagues to set up the Ktonal group. This group develops its own neural networks that are trained with audio data. The aim here is to utilise AI creatively to compose music – even if the programmed code is not so different from code that we already know from computers. »We take a pretty sober view of things,« says the 46-year-old. »It is really just addition and subtraction with a particularly high degree of complexity. You can think of it as a grid containing quite a few numbers. It then generates probabilities for the relationships between the numbers. And based on this probability data, something new is generated at the end – something that approximates the input data.«

The machine learns in much the same way as we humans do: it reads data, recognises special features or patterns in it and repeats the learning process several times. These iterative processes, these successive learning stages, are also known as »epochs«. And it’s precisely the intermediate stages along the way to the optimum result that seem attractive for creative work. »I’m interested in unfinished learning,« says von Lilienstern. »Because that often creates a special aesthetic of error – very similar to how I think it’s cute that my little daughter can’t speak properly yet. But you can also think about strategies for how AI can create a strange third element by feeding in different pieces of data that have nothing to do with each other at the outset. And suddenly the AI creates a hybrid of saxophone and the human voice, for example, or of a smoker’s cough and the shrieking laughter of two different people. The machine might then jump back and forth between the materials with virtuosity, building transitions where you would never have expected them."

ktonal: »Le Mystère des Voix Neuronales«

DIGITAL DADAISM

The way artificial intelligence recognises and learns connections is not dissimilar to human dreaming or free, imaginative association. Like a computer on drugs, AI forms new synapses. For Genoël von Lilienstern, this is a particular source of inspiration: »I can definitely see parallels with Dadaism or Surrealism. You have to find ways to end up in an aesthetic place that you couldn’t have imagined.«

Irish composer and voice artist Jennifer Walshe shares von Lilienstern’s view. The 51-year-old is interested in the imperfections of machine learning – just as language translation programmes still make mistakes and often inadvertently create wonderfully distinctive poetry. »I find it exciting when decisions are made that I can’t predict,« says Walshe. »Because as an improvising voice performer, I also like to work with other intelligences that make their own artistic decisions – whether they are humans or machines. Of course, machine learning systems always react in roughly the way we want them to. For example, you can ask a neural network to write a nice pop song and that’s exactly what will happen. But currently there are still crazy errors in the systems, so the programme might spit out an opera aria with someone suddenly yodelling in the middle."

As an artist interested in chance, she finds the early phase of machine learning systems particularly exciting. »Because it offers a new opportunity to come across strange things. Roughly speaking, to create a sound, the neural networks take a block of white noise. From this block, they carve out everything that doesn’t fit the sound they want to achieve. But as they aren’t perfect yet, there are always small particles left over somewhere. This is why AI often produces rather harsh sounds – with so-called glitches, small artefacts or high-frequency interference. It’s precisely these errors that are attractive for artistic work; a pity they are becoming increasingly rare.«

Jennifer Walshe: »ULTRACHUNK«

INSPIRINGLY PUZZLING

Even though the technology is improving faster than anyone can write texts on the subject, the typical AI glitch aesthetic still seems to be characteristic. For example, some of the pop songs released by OpenAI since 2020 sound like puzzling distortions of certain musical genres. An AI-generated song in the style of Frank Sinatra may seem frighteningly real, but on the other hand it produces digital artefacts, noise and strange transitions that inadvertently create a kind of experimental music. Exactly how such results are achieved remains a mystery – hidden in the black box of the AI system.

This mystery component is something that inspires Eva Reiter: »It’s not clear what principles the algorithm works by, what exactly happens in latent space,« says the 49-year-old Viennese composer. »The appeal lies in the fact that in some cases – especially when the system doesn’t work ›perfectly‹ – unconnected elements get recombined, and surprise me. Familiar chains of association then no longer work. And this immaturity, the ›misbehaviour‹ as something unexpected, is inspiring and reminds us that life is fundamentally subject to contingency, that everything could be completely different. So it’s the ›fantastic precision‹, as Robert Musil called it, and not the ›pedantic‹ precision that interests me.«

Reiter sees the integration of AI and interactive music technologies primarily as an opportunity for expansion. »It gives us the chance to enter into an extended creative discourse with a digital companion, a kind of mirror where we recognise ourselves in a slightly distorted form. We gain insights into ourselves that are disconcerting, amusing and unexpected.«

Jennifer Walshe sees the machine along the same lines as a creative counterpart with which her own creativity can resonate. One of her projects, »A Late Anthology of Early Music«, emerged from an AI-generated cross between the sound of her own voice and recordings of Early Music: compositions by Guillaume de Machaut, Carlo Gesualdo and others were fed into it. The result is absolutely enigmatic music that can’t be pigeonholed in one genre. For this project, Walshe collaborated with the US-American programming duo dadabots.

NEW QUESTIONS, OLD EXAMPLES

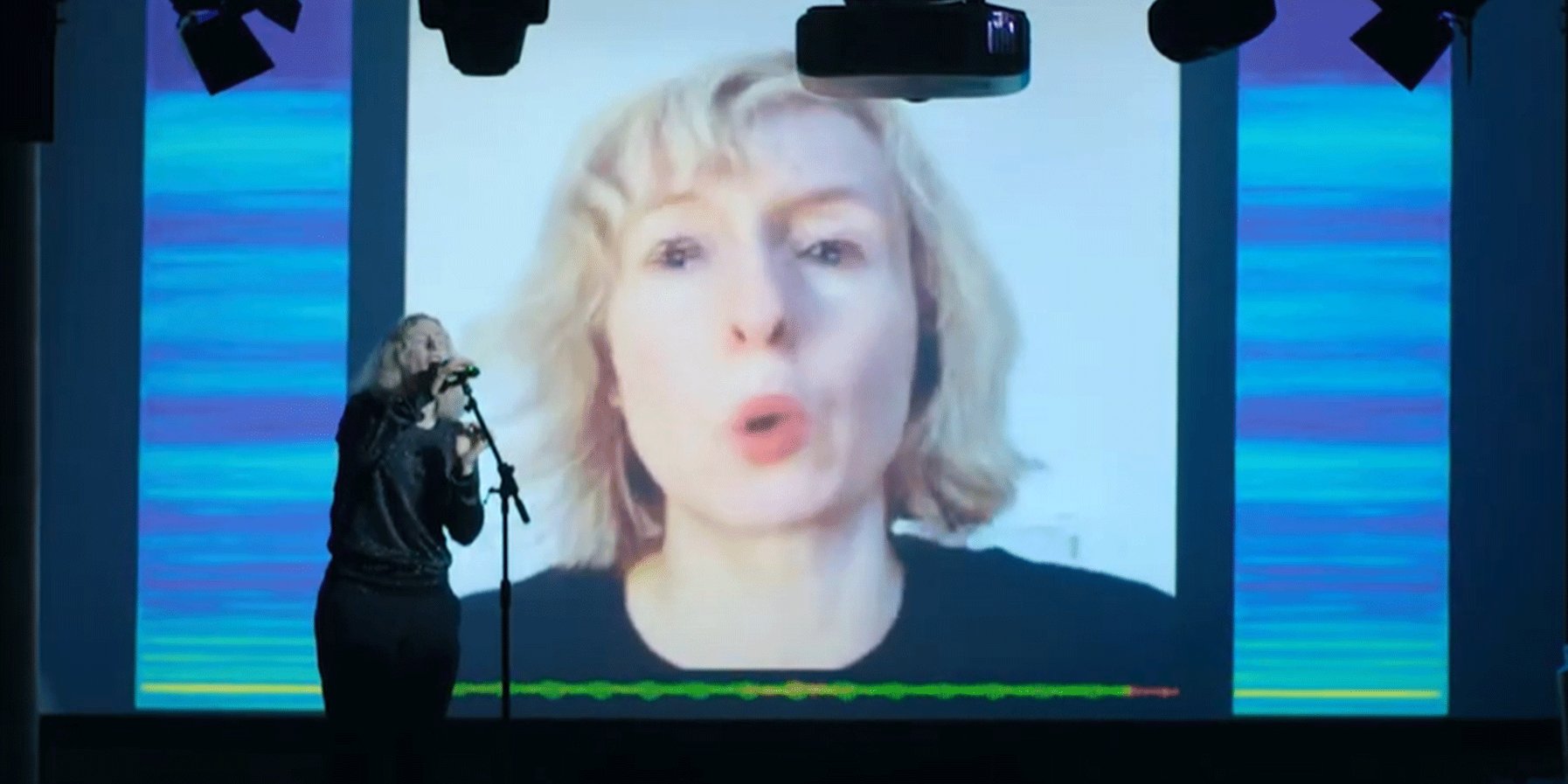

In any case, it often seems to be joint projects that give rise to contemporary AI compositions, as in Brigitta Muntendorf's case. »Together with the Ukrainian collective Respeecher, I have been working with voice cloning processes for some time,« says the 42-year-old. »For example, I record the vocal sounds of a singer and create a model to train the AI. Theoretically, I can then make the singer’s voice sing all kinds of things.«

Of course, such an approach also harbours the risk of misuse: »This raises completely new questions relating to authorship. The Ukrainian company’s basic model already consists of thousands of cloned voices – both self-recorded and found online. They need this to make the voice AI work at all. But of course it isn’t without controversy. That’s why the collective has also drawn up a comprehensive ethics compendium. You have to ask questions like these: How can a singer’s voice be protected? How is the person remunerated if their cloned voice is used somewhere? How can we prevent new things from being generated using a voice without the owner’s consent? The danger of digital colonialism is part of this new reality, and that’s something we have to deal with.«

Looking at the current situation, it’s easy to forget that making music with artificial intelligence is not completely new. 1957’s »Illiac Suite« by US composer Lejaren Hiller is often cited as an important historical milestone – a computer-generated string quartet score that is considered to be the very first of its kind. However, it is not entirely clear how much additional selection and structuring work was done by humans.

In general, however, the idea of involving another, non-human medium or tool in the composition process underwent a boom in the decades after the Second World War. This also applies to algorithmic composition - a process in which the score is generated by an automated, mathematically describable process. The prerequisite for this is that the composer defines a series of materials and rules in advance. One of the pioneers in this field was Gottfried Michael Koenig, who was not only a composer but also an expert in recording studio and computer technology.

Lejaren Hiller: »Illiac Suite«

LIQUEFIED, NOT MADE REDUNDANT

You don’t have to be a qualified IT expert to work with artificial intelligence as a musician today, but it can’t do any harm. Alexander Schubert, for example, studied computer science before training as a composer, so he has been involved with artificial intelligence for a long time. One of his preferences – especially in audiovisual projects – is the »softening« or recomposition of identities: »At a tonal level, this can mean, for example, that a noisy string sound changes directly into a human scream. And at a visual level, I like to generate hybrids of different people, such as the members of an ensemble. This can result in something that moves like a person but is no longer clearly identifiable as a woman or a man.«

In this way, Schubert »liquefies« typical characteristics of different people or sounds and timbres, creating bizarre mixtures. Our perception is challenged, because we can’t make any progress using the categories we have learned for classifying sensory stimuli. Such approaches seem to be popular with many composers at the moment. No wonder: contemporary music has long been experimenting with throwing old systems of classification overboard – in favour of a new perception that may be finer and more differentiated.

Despite all the worrying developments in technology, musicians have found ways to utilise artificial intelligence productively. And most of them feel relaxed about the possibility of their own redundancy. After all, AI can sort and order things, but artists still have to come up with creative ideas and develop decision criteria, make aesthetic judgements and reach conclusions themselves. Eva Reiter puts it in a nutshell: »AI doesn’t make good composers worse and mediocre ones better. It can create access and level out hierarchies. It can render some work processes more efficient, but it still doesn’t enable a user to take short cuts. It cannot compensate for indecisiveness – and certainly not for a lack of artistic vision.«

This article appeared in the Elbphilharmonie Magazine (issue 2/25).