Text: Robert Rotifer, April 2025

The Australian singer-songwriter Nick Cave once said that it’s »a good thing« when an artist »challenges the people who like their music to a certain extent. Maybe they should realise that they might actually be wrong in their assumptions about a certain type of person with a certain type of history.«

Nick Cave is an institution – a figure who lives in the collective imagination of his fans. He’s well aware of this and lives with it. From his instantly recognisable voice to his lanky silhouette in signature suits and his catalogue of classic songs played at both weddings and funerals, everything about him feels like part of the cultural furniture. It would be easy to overlook what a walking paradox he actually is.

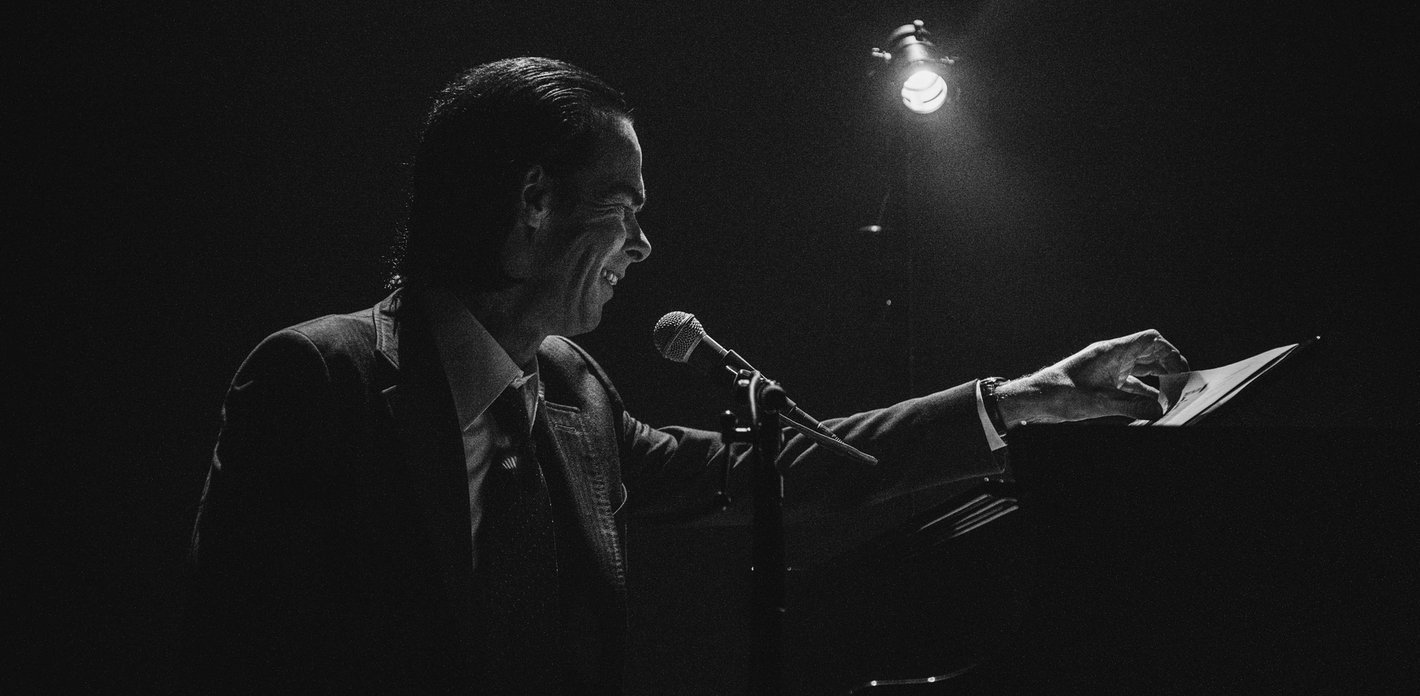

Nick Cave im Portrait

In his early days, Cave was heroically revered as a romantically eccentric junkie. These days, he has evolved into a kind of moral authority, a spiritual guide whose website, Red Hand Files, offers his fan base comfort and advice in difficult times. On New Year’s Day, he rather unctuously suggested that we lean into the principle of hope, despite the catastrophic state of the world. He has even explained the meaning of death in his songs to a group of Corsican schoolchildren, tracing its presence from the raw violence of his early work – portrayed as repressed emotion – to the elegiac quality of his more recent music, shaped by the tragic loss of his son Arthur a decade ago: »Feelings of loss and guilt ran through everything.«

This kind of emotional vulnerability lends Cave the credibility of a confidant – but such intimacy seems only possible within the shelter of his (old-fashioned format) personal website. His approachable online persona would be unimaginable in the arenas of performative misunderstanding run by the tech oligarchs, which is why Cave consistently shuns these portals.

»Wild God«

So wie er sich auch keiner Kirche zuordnen lässt, wiewohl er sich immer wieder auf Gott und die Bibel beruft. Manchmal wirkt er dabei frömmelnd wie ein Priester, siehe »As the Waters Cover the Sea«, die barocke Auferstehungsgeschichte am Ende seines jüngsten Albums »Wild God«. Dann wieder begegnet er der eigenen Spiritualität geradezu spöttisch, etwa im Titelsong desselben Albums, in dem ein frustrierter, wilder Gott mit »langem, fließendem Haar« per Abflug durchs Fenster dem Schrecken seines Altersheims entflieht.

Instinctive free spirit

The man who writes such lyrics is an instinctive free spirit, but also harbours an equally instinctive conservatism at his core. »Conservative with a small c,« as he likes to put it. With a disciplined work ethic, Cave answers fan mail, writes songs, composes film scores, sculpts devil figures inspired by Staffordshire ceramics, and devours podcasts for hours on end. On the surface, his music fits the traditions of dignified adult rock, yet for some time now, his recent compositions and arrangements have often relied on digital loops crafted by his long-time collaborator Warren Ellis. So at 67, Cave can hardly be described as a technophobe.

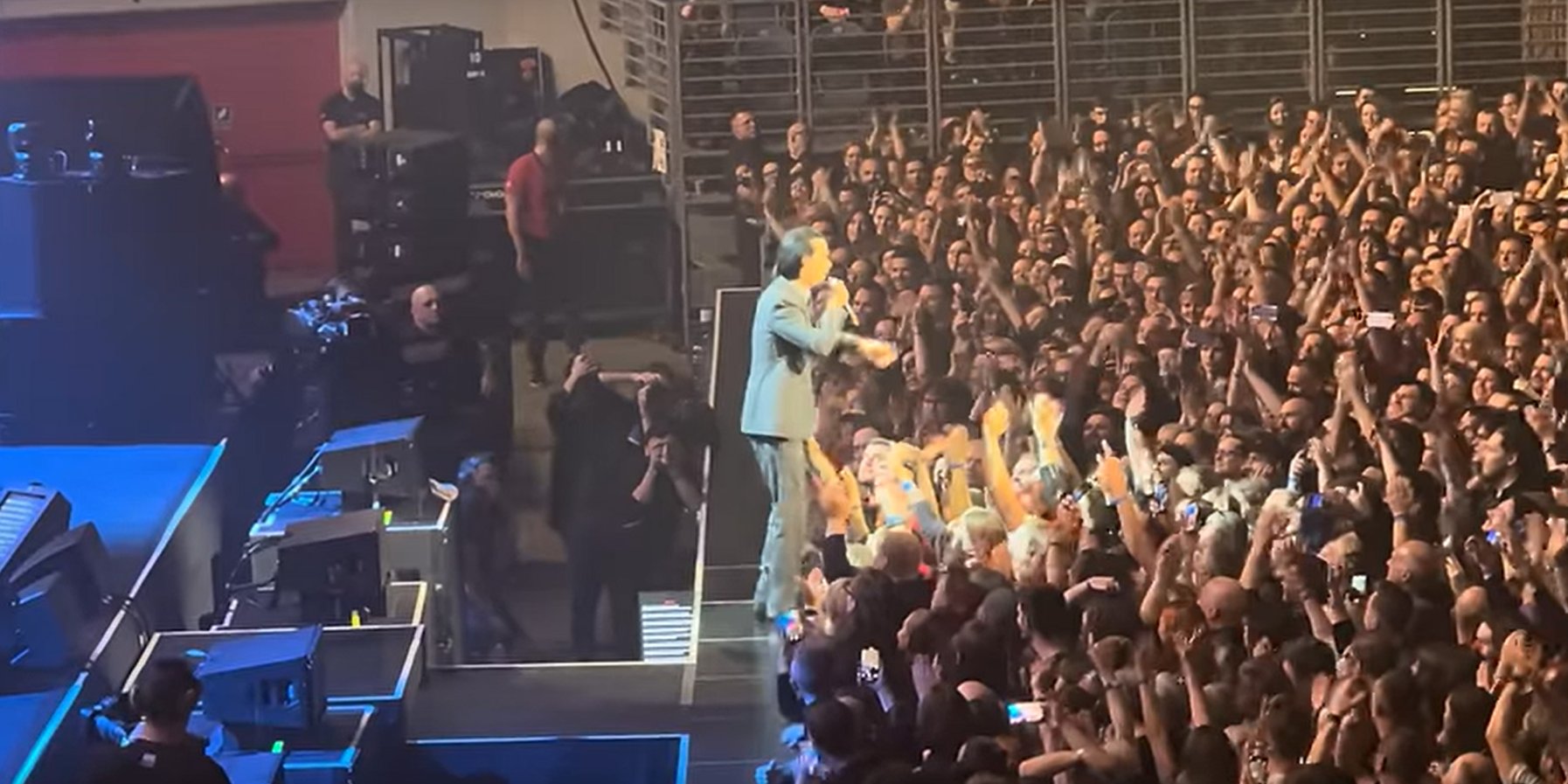

And yet it was entirely in keeping with Nick Cave’s vintage brand when, at a concert with his band Bad Seeds in Krakow last year, he told his audience with energetic conviction put their »fucking phones« away. The irony was that Cave’s intervention against the digital obsession with immortality only went viral because a YouTuber named Mr. Jazzowo filmed the maestro’s admonishing words from his balcony (racking up nearly a million views and 2,400 heartfelt comments supporting Cave’s stance).

Nick Cave: »Put your fucking phones away!«

We owe Larry Rulz 5 (18,400 followers), a user specialising in live recordings, for the 109,000 views of a much more intimate performance: Cave’s concert at the sold-out Beacon Theatre in New York (capacity: 2,600 seats) in October 2023, accompanied only by his own strictly functional piano playing and Radiohead’s Colin Greenwood on bass. That same duo is set to perform twice in June 2025 in the slightly smaller Elbphilharmonie Grand Hall.

Those who managed to get tickets would be well advised to avoid watching this recording, so as not to deprive themselves of what Nick Cave very aptly describes as »one of the last transcendent experiences we have left«: music as direct communication between the artist, their fellow musicians and the audience, in the same space at the same time, including all the simultaneous interactions that arise.

Nick Cave & Colin Greenwood at the Beacon Theatre (2023)

Small songs and big songs

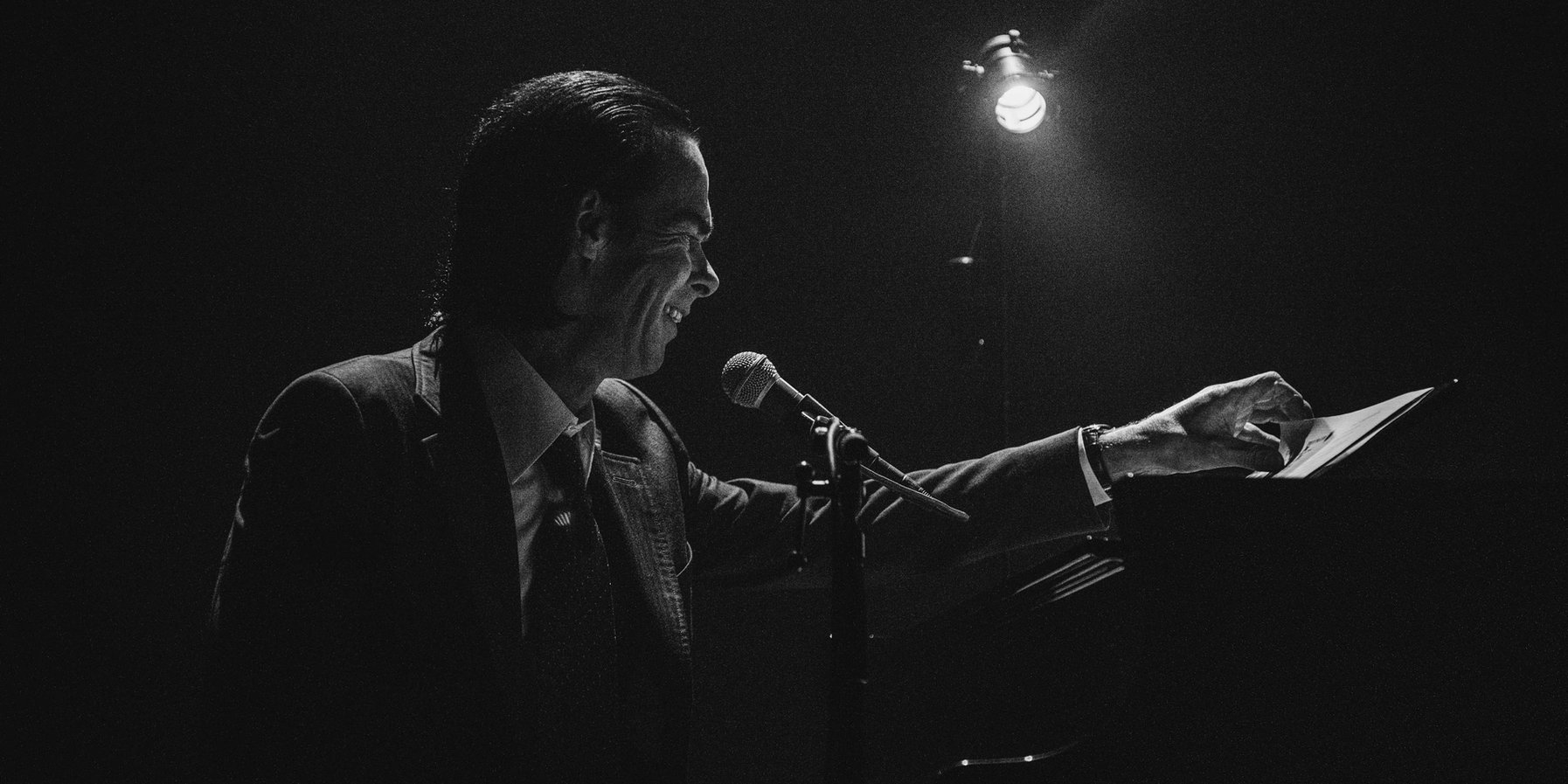

That said, Cave’s announcement after »Girl in Amber«, the opening song of his New York set, immortalised in the aforementioned video recording, is a moment worth preserving. Rising briefly from his piano stool, he succinctly explains the concept of this particular show: »We’re going to try to give a concert of ludicrously reduced versions of the songs you love…« (applause, cheers and shouts of »Yeah!« from the audience) »…in a way that you may not love.« The audience laughs, but Cave’s tone remains serious. »We’re going to try, as it were,« he continues, »to look inside the songs to see how they work and what comes out.« With that, he sits back down at the piano and launches into a generous set list that traverses his whole career, from famous hits to neglected niche gems – what he himself calls »little songs and bigger songs«.

A few songs later, after the distance between him and the audience has all but dissolved, Cave adds: »Basically, I write a lot of songs that the band never picks up because they’re small and unimportant and can’t compete with the bigger songs. For every one of those bigger songs you love, there’s a whole bunch of tiny songs that get trampled by them.« Then he plays »Euthanasia«, an enchantingly unspectacular work that first appeared in »Idiot Prayer«, the film of his solo concert performed in the yawning emptiness of London’s Alexandra Palace during the 2020 pandemic lockdown. It’s easy to see what Cave is trying to show us: it takes the small songs to make the bigger ones seem big.

Conversely though, the reduction of his songs to a concentrate of basic chords, vocals and sparingly placed bass notes (because Greenwood understands what it’s all about) also reveals the deep kinship and continuity between the works from various creative phases of the past five decades: From his punk band The Birthday Party, which left distant Melbourne for London in 1980, and the frenzied, neo-Gothic blues of the early Bad Seeds, through his sober catharsis on albums such as »The Boatman’s Call« (1997) and the productive midlife crisis of the Grinderman period, to the existential albums, free of cynicism and, for the most part, irony, after Arthur Cave’s death (»Skeleton Tree«, »Ghosteen«, »Carnage« and »Wild God«) – a unifying thread of human tenderness hidden beneath becomes apparent in retrospect. With each song, as Cave tosses the lyrics from the music stand to the floor, he reveals the story of an artist whose life has been consumed by an almost compulsive creative drive.

Artificial humour

This brings to mind an anecdote Cave shared last year about his experiment with the AI web application Suno, which generates pop songs from keywords. »Someone said to me, ›Try this,‹« Cave told the author in an interview in London, »so I typed, ›Write a slow, dark gothic song about a banana.‹ Fifteen seconds later, this song appears, and it’s really good. It’s called »The Dying Peel«. According to Cave, the AI showed »a sense of irony«. »It understands that you’ve made a little joke, so it also makes a joke in the lyrics about the peel and flesh turning black as the banana ages. And all that with a catchy chorus thrown in. Amazing.«

But then he tried the same trick again. »I typed something like, ›A death metal song with a huge choir about the Nanjing Massacre‹. And again, a song came out, but by then I was already bored with the whole exercise.« In just six minutes, his emotional response to the song generator’s music had shifted »from overwhelmed to bored«. »And after that, I was just disgusted. What’s really happening here is that these tech people are getting rid of the concept of artistic effort itself. The idea that an artist has to sit down, hatch a tiny idea and turn it into something beautiful is just an inconvenience on the way to the product, so let’s get rid of it. Art is reduced to a mere commodity and thus made completely banal and meaningless. The disgusting thing about it is that this is actually how the world is right now. The world we live in doesn’t care about stuff like that. Maybe five years ago it would have caused a stir, but I think in the end, nobody gives a shit.«

Everyone except that not insignificant minority who sits in a hall like the Elbphilharmonie for two hours to listen to a man who, with nothing but a piano and the moral support of his bassist, shows us exactly what artistic endeavour looks like. In doing so, he achieves something the Suno app never could: he dives deep into the songs, uncovering how they work and what comes out.

This article appeared in the Elnbphilharmonie Magazine (issue 2/25)