Text: Regine Müller, April 2025

John Cage is one of those artists who defies traditional genre labels. While he’s often categorised first and foremost as a composer – and he certainly reshaped the landscape of modern music in the latter half of the 20th century. His seminal impact stems less from work within the confines of what is commonly referred to as composing. Instead it is down to his unbiased way of thinking, asking fundamental questions and bringing surprising concepts to life that startled and inspired. His thinking was marked by his ability to drift apparently aimlessly through life, paired with a sharp and boundless receptiveness, allowing him to explore freely and commit deeply wherever he sensed there was terrain with real potential.

John Cage’s life story reads like a never-ending chain of remarkable encounters – an almost encyclopaedic journey through Western modernism. From studying with Arnold Schönberg, mingling with Bauhaus luminaries and engaging with New York’s avant-garde scene around Peggy Guggenheim, to collaborating with Karlheinz Stockhausen and Yoko Ono, his path of ideas intersected with many of the century’s creative giants. Born in Los Angeles in 1912 and passing away in New York City in 1992, Cage was a lifelong explorer, though never with the tragic attitude of being destined to exile. Instead, his approach was marked by lightness and curiosity – playful, inquisitive, and always reaching beyond the confines of label, style or genre.

Dance piece for improvised percussion

This is what makes Cage’s body of work so elusive. An absolute all-rounder, he oscillated effortlessly between action and conceptual art, poetry, painting, mycology, philosophy and music. Many of his works exist in the hazy, grey spaces of »no longer« and »not yet,« resisting clear categorisation. Cage himself described his very first composition as a by-product of a holiday on Majorca, during a period when he was equally immersed in painting and poetry. »The music I composed followed a mathematical method I no longer recall,” he once said. »It didn’t feel like music to me, so I left it behind when I left Majorca, not wanting to weigh down my luggage.«

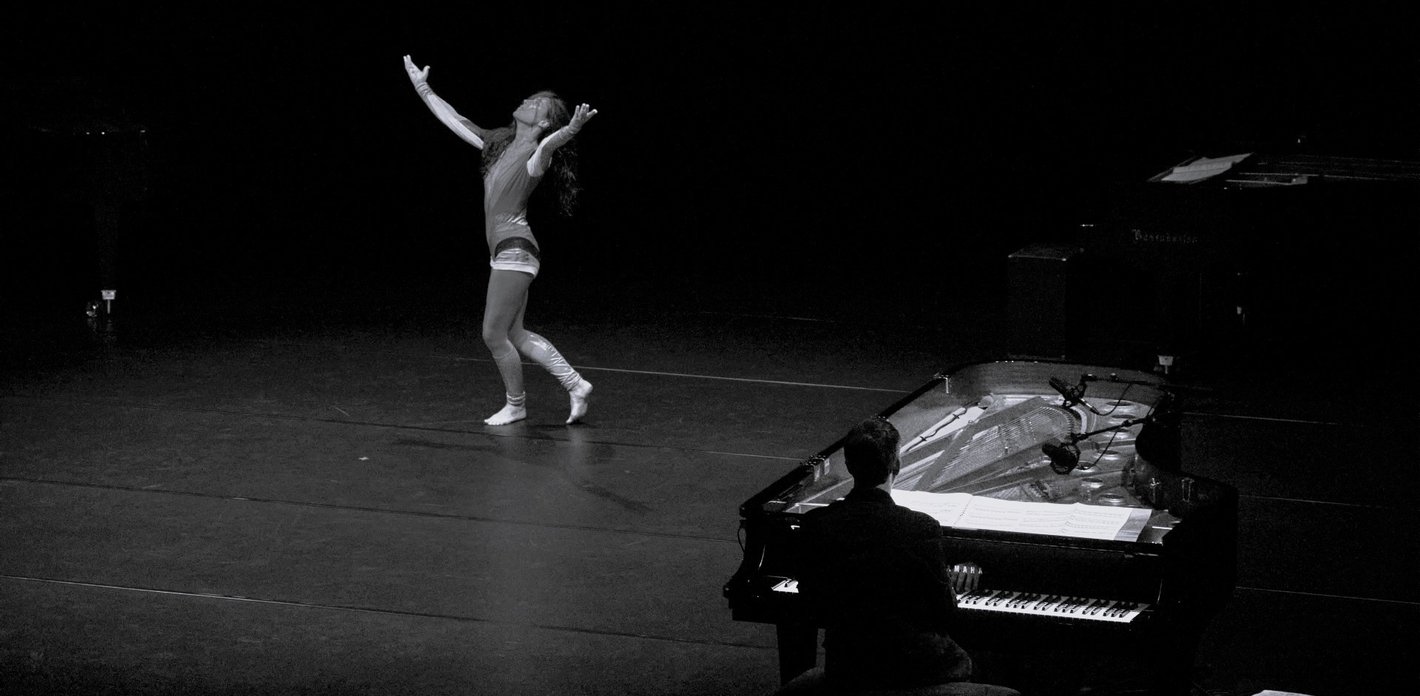

The performance »Cage²« by pianist Bertrand Chamayou and dancer Élodie Sicard explores one of the many pivotal moments in John Cage’s artistic evolution. Together, they engage in an experimental dialogue that pairs a selection of Cage’s early works for prepared piano with choreographed dance – a concept that brings the music full circle to its origins, as these compositions were initially conceived for dance.

The very first work in this series – »Bacchanale«, composed between 1938 and 1940 – was a dance work commissioned by the African-American dancer Syvilla Fort. Cage had envisioned using a percussion ensemble to evoke sounds inspired by indigenous and Asian music. The »invention« of the prepared piano was actually something he came up with on the fly, as Chamayou reports in a phone interview: »The room where the performance was to take place turned out to be far too small for the planned percussion ensemble. So Cage had to find a solution for »Bacchanale« very quickly by improvising. He already had very vivid ideas in his mind, so he began preparing the piano to mimic percussive sounds. It was an incredibly effective solution.«

A »utopian piano concert«

Cage prepared the inside of a grand piano using everyday materials from the DIY store. Drawing inspiration from his teacher Henry Cowell’s experiments, he inserted felt, metal and rubber objects between, on or beneath the strings of a grand piano. This radically altered the instrument’s sound, opening up an entirely new world of sound.

Following »Bacchanale«, Cage composed several more pieces for dancers and choreographers, including works for his future partner Merce Cunningham and then company collaborator Jean Erdman. In his early forties, his artistic outlook was deeply shaped by non-Western music and Zen Buddhism. The titles of his prepared piano works for dance also reflect his preoccupation with pressing political issues of the day, such as »Our Spring Will Come« (1943), which echoed the mood of protest to racial segregation in the USA at the time, and »In the Name of the Holocaust« (1942).

Among the twelve works chosen for »Cage²« – all composed between 1940 and 1945—there are also poetic passages and flashes of light-hearted humour. Bertrand Chamayou describes the selection as »a utopian piano concert« or even a kind of »cabaret«: »Like twelve images, twelve scenes, twelve moods. The audience applauds in between. It’s a very fragmented format that perfectly captures Cage’s spirit.«

Choreography as a doubling

The idea of staging this music theatrically occurred to Chamayou during a performance at the Lucerne Festival, where he presented a programme featuring works by Ravel and Cage: »I felt something was missing – an extension of my pianistic gesture into something choreographic. I imagined a kind of doubling. The idea just wouldn’t leave me.« At that point, it remained a purely theoretical idea, as only the traditionally notated piano scores from Cage’s collaborations with his choreographic partners have been preserved. No written or filmed records of the original choreographies exist.

Together with dancer and choreographer Elodie Sicard, an entirely new choreography was developed for Cage². »The music is already very strong on its own – we’re working with twelve very distinct characters,« says Chamayou. Sicard responded to the music with spontaneous, intuitive improvisation. Every step of the development phase was filmed, capturing each idea, its evolution or rejection, and every correction. »Whenever a gesture resonated with us, we discarded everything else and gradually assembled the moments that worked. In the end, we had a visual montage from which Elodie precisely crafted the final choreography.«

Bolts, screws, rubber dampers

The choreography originates from improvisation and spontaneous movement, yet it was later meticulously documented in a detailed gestural score. While both Chamayou’s piano playing and Sicard’s dance convey a sense of spontaneity, this effect is a carefully crafted illusion. The production is, in fact, tightly controlled with little room for actual improvisation. Chamayou points out an intriguing contradiction in this context: »When we think of Cage, we usually associate him with improvisation and, above all, with chance as a fundamental structural principle. But these works were composed quite early on, during a period when his writing was still very precise. The music is rhythmically exact and traditionally notated, quite unlike some of his later works that use more graphic notation.«

Chamayou sees Cage’s works for prepared piano as marking a pivotal shift in the composer’s artistic direction. »His conceptual thinking begins right here, with the very idea of preparing the piano. It’s also where the element of chance first enters his music, through the acceptance that the result sounds different every time.« While Cage did draw up a so-called preparation table, listing the exact size and placement of screws, bolts and rubber dampers inside the piano, every prepared instrument ends up sounding unique. And the result no longer resembles a piano in the traditional sense. Instead, it conjures sound worlds far beyond the Western canon. »It feels like a journey across the globe,« says Chamayou, »from Africa to Japan, from Buddhism and Taoism to the Sufi music of Persia and the Middle East. The piano, once a symbol of Western classical music, morphs into something entirely new through its scales and sonic colours.«

In order to create the strange, exotic sounds demanded by Cage’s compositions, ample time is needed to prepare each piano according to his detailed instructions. For this reason, »Cage²« features four differently prepared pianos on stage. Positioned at each corner, they form a square – in visual reference to the title for this evening. It also alludes to the duo at the heart of the performance: one pianist and one dancer.

Chamayou notes that when Cage began composing works for prepared piano, he was far from being a fully developed, accomplished composer. Yet that is exactly what makes his work so compelling. »His limited technical skills and expressive tools, his lack of formal compositional training at the time – that was his strength. Cage had a vivid imagination and used it resourcefully to articulate his ideas. He was undoubtedly a significant composer, but more importantly, he was a major artist – because he dared to ask fundamental questions.«

This article appeared in the Elbphilharmonie Magazine (Issue 2/25).

- Elbphilharmonie Kleiner Saal

Bertrand Chamayou, Piano / Elodie Sicard, Dance – Hamburg International Music Festival

Past Concert